| Origin | Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) |

| Insertion | Medial surface of proximal tibia, medial to tibial tuberosity (insertion is part of pes anserinus) |

| Action | Flexion of the knee Flexion of the hip Abduction of the hip Lateral rotation of the hip Medially rotates tibia when knee is flexed |

| Nerve | Femoral nerve, anterior division (L2, L3, L4) |

| Artery | Femoral artery |

Location & Overview

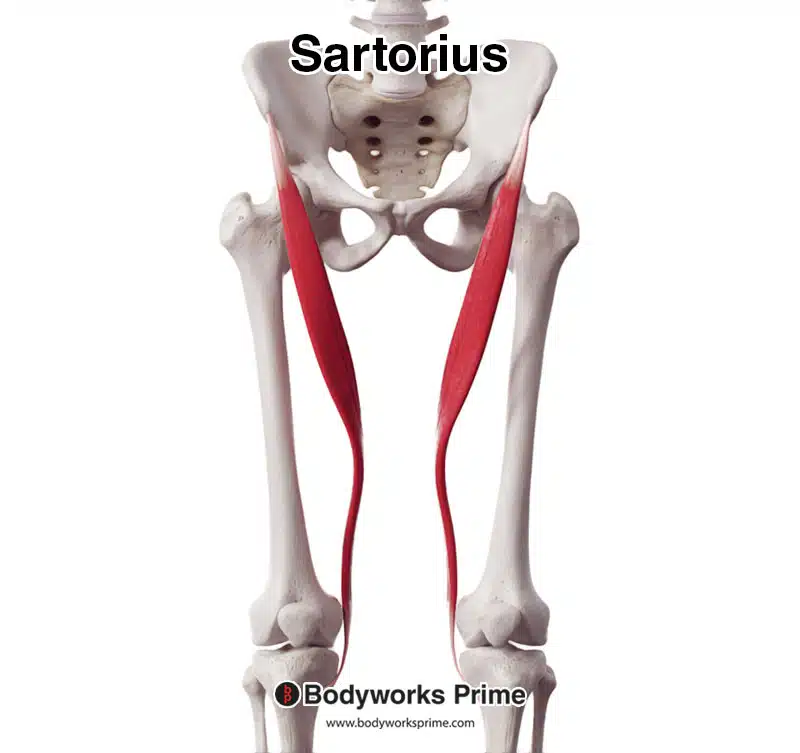

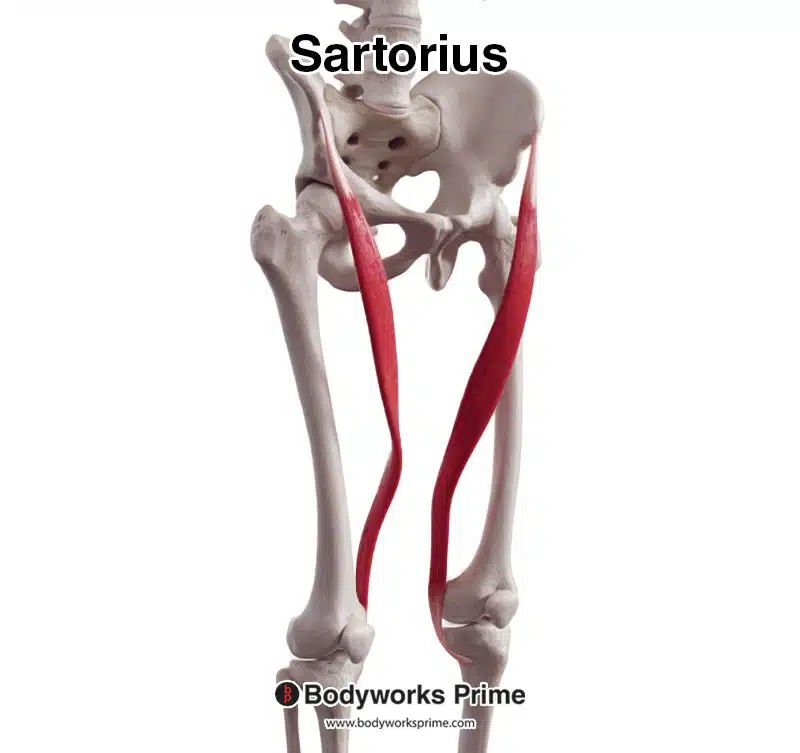

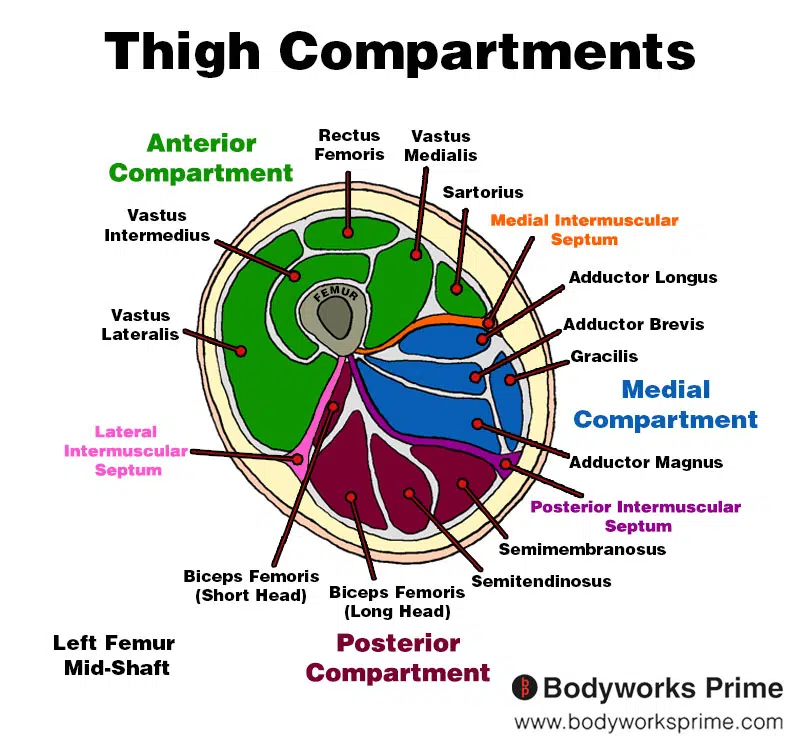

The sartorius muscle is recognised as the longest muscle in the human body, positioned anterolaterally in the thigh, with its path crossing both the hip and knee joints. It prominently resides in the anterior compartment of the thigh. It assumes a unique diagonal orientation, stretching from the lateral aspect of the hip, crossing over the thigh’s superoanterior portion, and then descending down toward the medial side of the knee. Its unique location enables it to play a role in the movements of both of the hip and knee joints. This muscle is a superficial muscle, located close to the skin’s surface, which makes it easily palpable and visible in lean individuals [1] [2] [3] [4].

In terms of its location comparative to other muscles, it is situated anterior to the quadriceps femoris muscle and posterior to the fascia lata, a deep fascia of the thigh. Medially, the sartorius muscle neighbours the adductor longus, and laterally it borders the tensor fasciae latae muscle. The muscle’s unique diagonal orientation distinguishes it from other muscles of the thigh region, which predominantly run vertically [5] [6] [7].

The term “sartorius” is derived from the Latin word ‘sartor’, which means tailor. This name is believed to originate from the cross-legged position that tailors historically adopted while working. The sartorius muscle, when contracted, enables such a position by flexing both the hip and knee joints and externally rotating and abducting the hip [8] [9].

Here we can see the sartorius muscle seen from an anterior view.

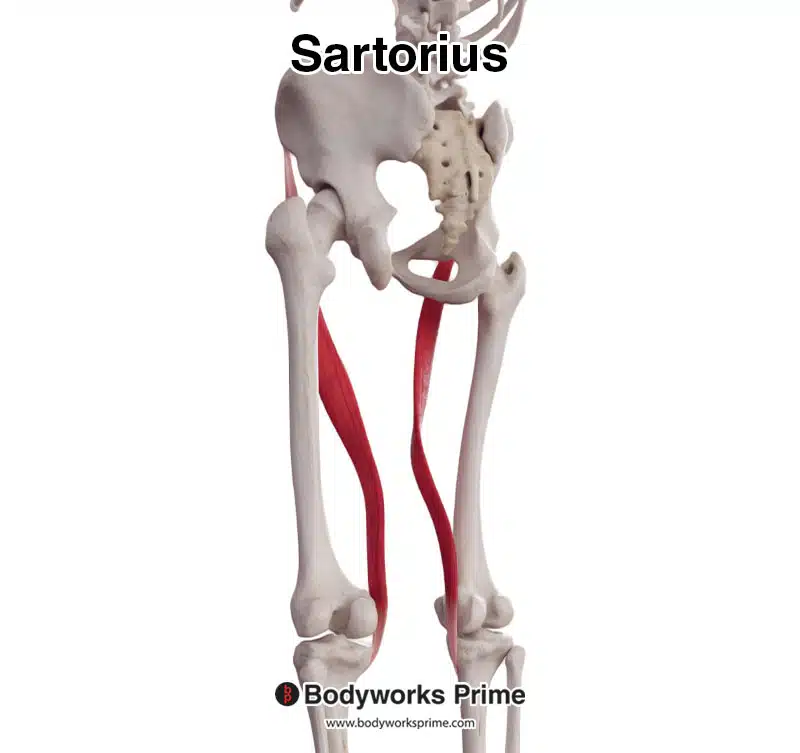

Here we can see the sartorius muscle seen from an anterolateral view.

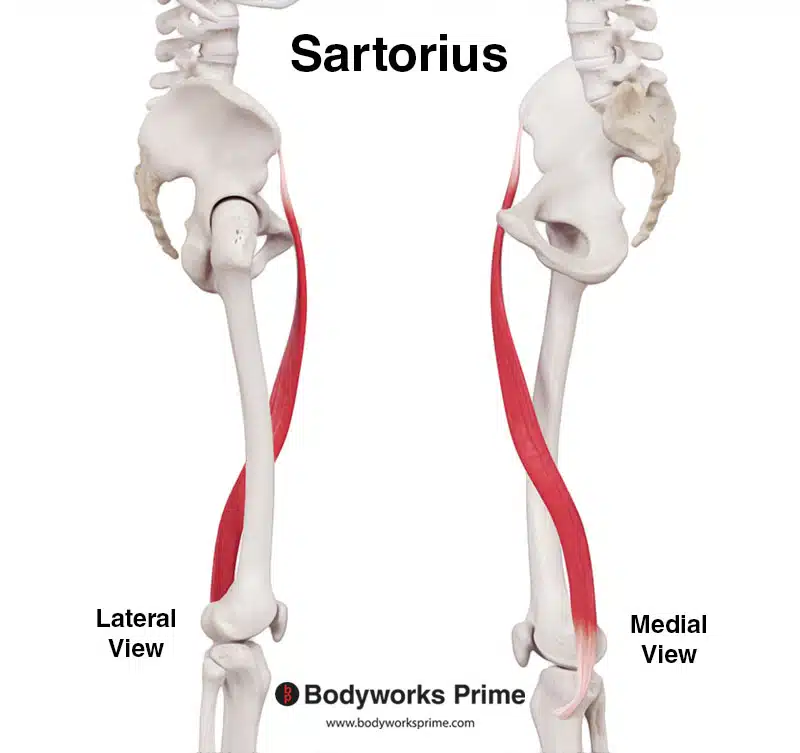

Here we can see the sartorius muscle seen from a lateral and medial view.

Here we can see the sartorius muscle seen from a posterolateral view.

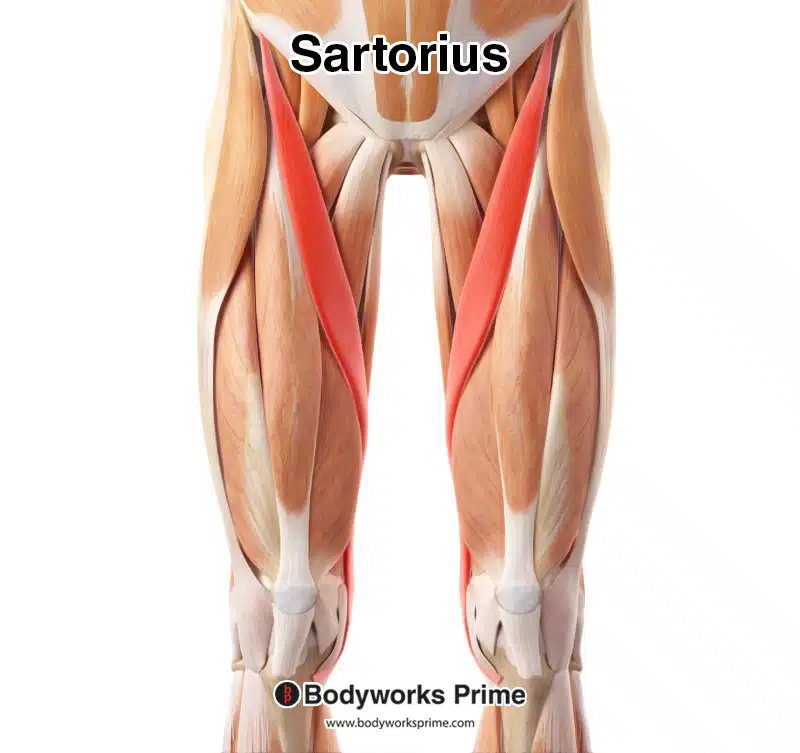

Here we can see the sartorius muscle highlighted in red, amongst the other muscles of the body, seen from an anterior view.

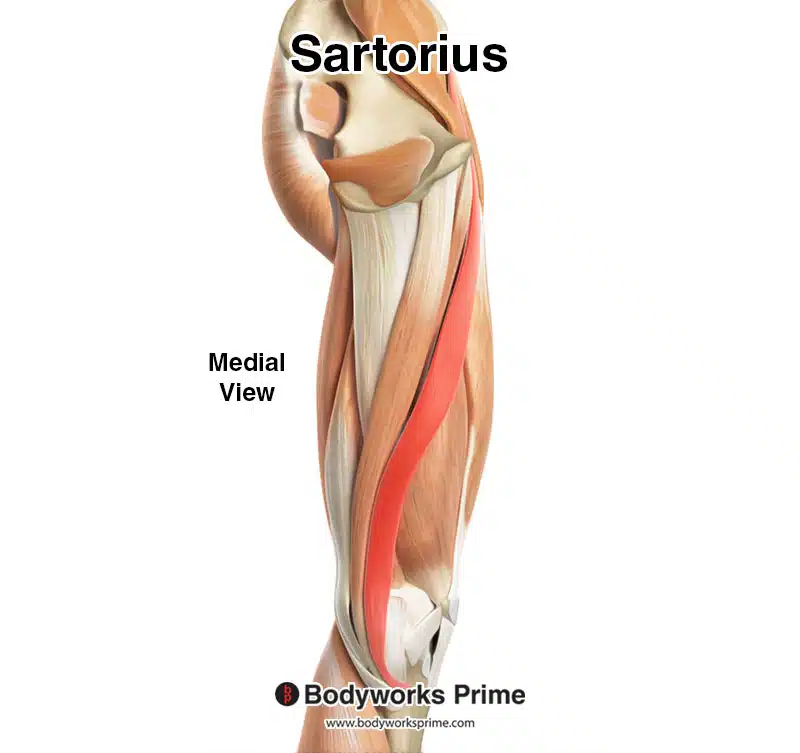

Here we can see the sartorius muscle highlighted in red, amongst the other muscles of the body, seen from a medial view.

Here we can see an image of the compartments of the thigh. We can see the sartorius in the anterior compartment, the section coloured in green.

Origin & Insertion

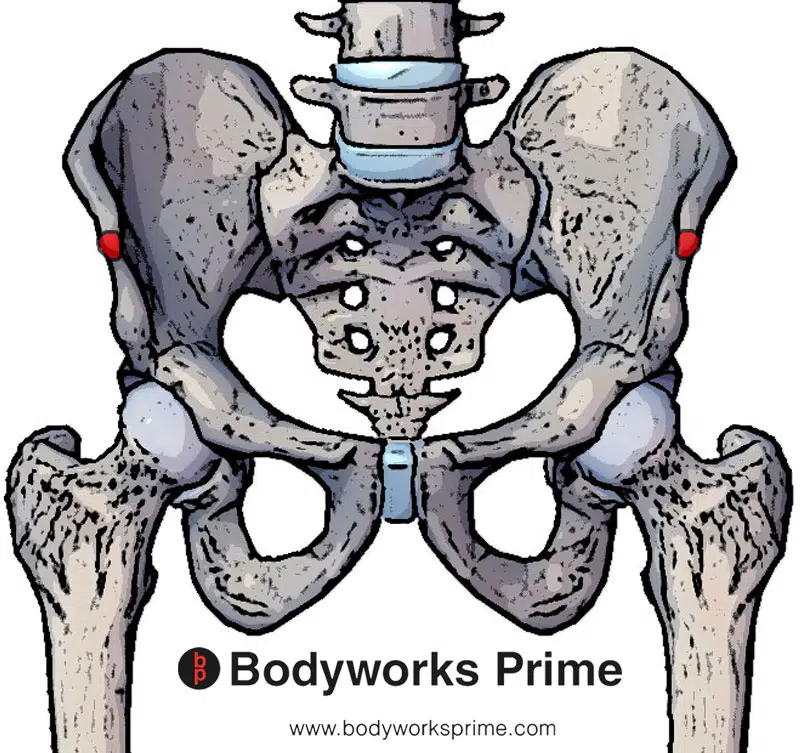

The sartorius muscle originates from a bony prominence of the pelvis which is known as the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). The ASIS is a palpable and prominent bony point located at the front and top of the ilium. The ilium is the largest of the three bones that make up the hip bone [10] [11].

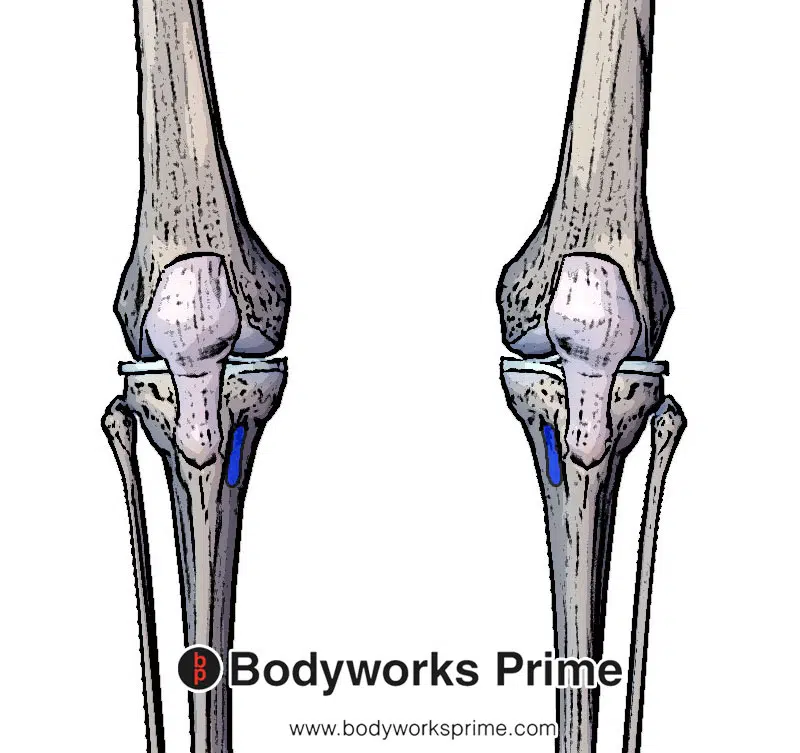

From its origin, the sartorius extends inferiorly, crossing the front of the thigh diagonally to insert medially at the knee. Its insertion point is the medial surface of the proximal part of the tibia, medial to the tibial tuberosity. The tibial tuberosity is a palpable bony prominence found just below the kneecap and serves as the attachment point for several tendons (such as the quadriceps tendon) [12] [13]. This region of the sartorius’ insertion is often referred to as the ‘pes anserinus’, or ‘goose’s foot’, due to the combined insertion of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus tendons, which bear a resemblance to a goose’s foot [14] [15].

Here we can see the origin of the sartorius muscle highlighted in red.

Here we can see the insertion of the sartorius muscle highlighted in blue.

Actions & Function

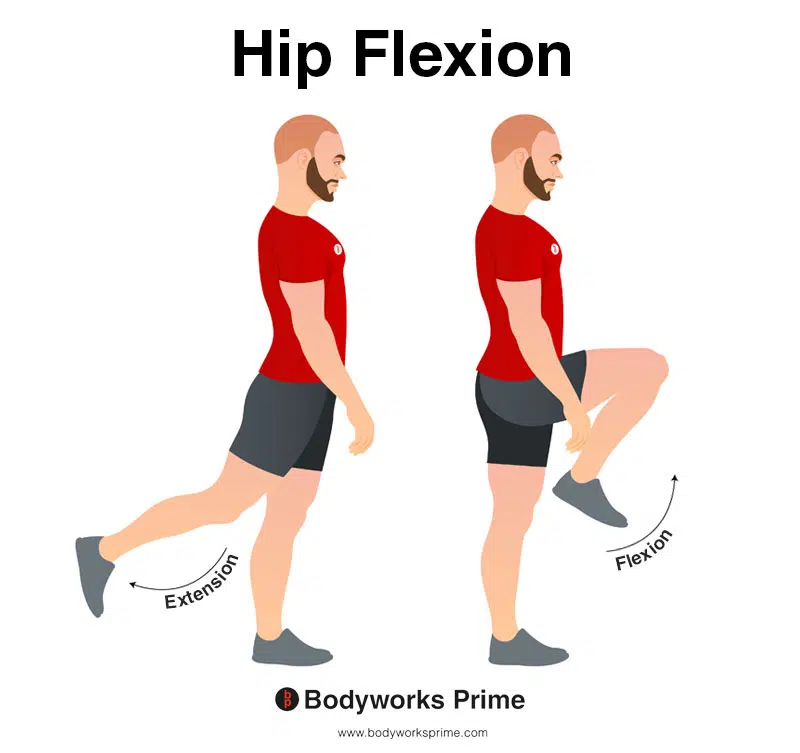

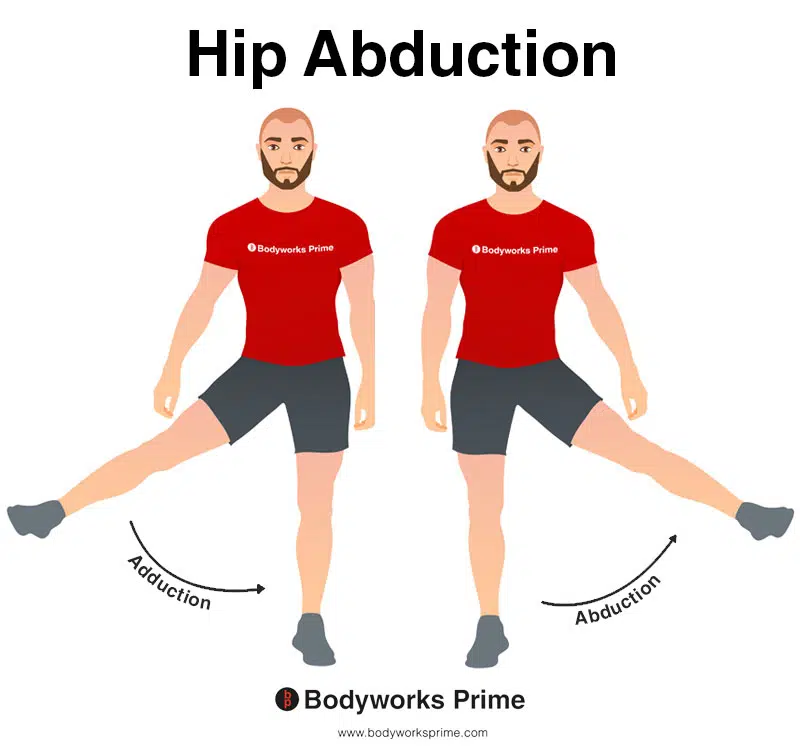

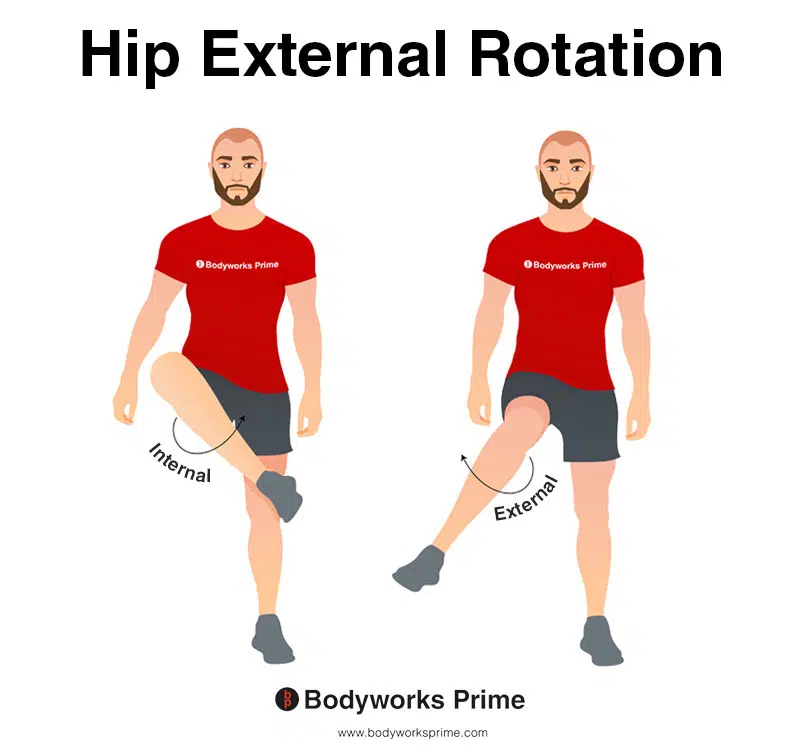

The sartorius muscle is versatile and capable of acting on both the hip and knee joints due the unique way it crosses over the thigh. At the hip joint, the sartorius functions in flexion, abduction, and lateral rotation. Flexion of the hip, facilitated by the sartorius, involves reducing the angle between the thigh and the torso, akin to lifting the knee towards the chest [16] [17]. Abduction, another action at the hip, involves moving the leg laterally, away from the midline of the body, like when spreading the legs apart while standing [18] [19]. Lastly, the sartorius also contributes to the lateral rotation (external rotation) of the hip. This movement involves turning/rotating the thigh outward [20] [21].

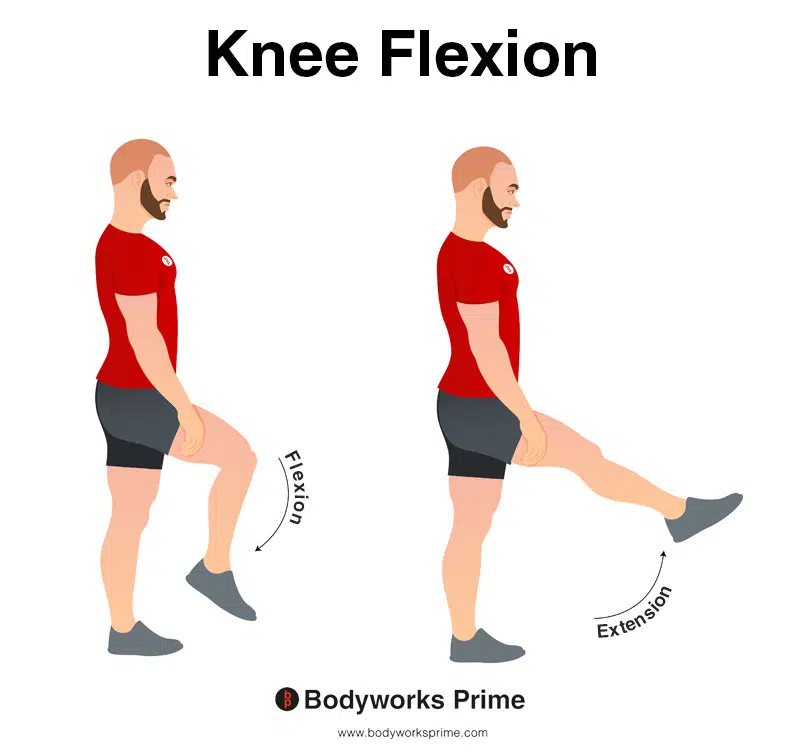

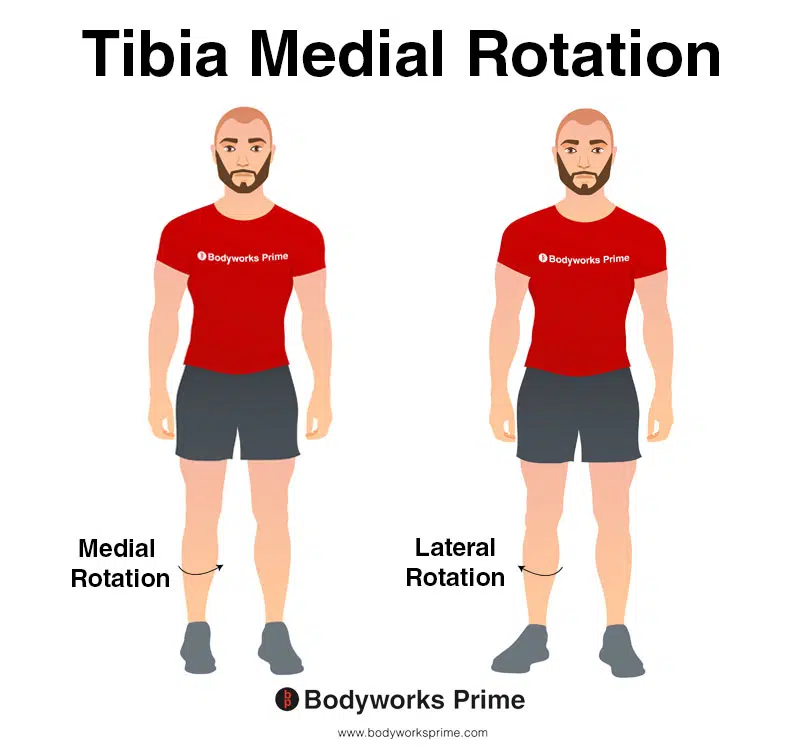

At the knee joint, the sartorius assists in flexion and medial rotation. Flexion of the knee is the action of reducing the angle between the lower leg and the thigh, similar to bending the knee as you swing it back to kick a football [22]. Medial rotation (internal rotation), on the other hand, involves turning the tibia (shin bone) inward while the knee is flexed, an example of this would be turning the foot inward when keeping the thigh still. You will notice the shin rotates slightly inwardly too, which would be medial rotation of the tibia [23].

In this image, you can see an example of knee flexion, which is the action of bending your knee. The opposite movement of knee flexion is knee extension. The sartorius can flex the knee joint.

In this image, you can see an example of hip flexion, which is the action of raising your leg up in front of you and causing your hip to bend. If both legs are fixed, the torso will lean forward towards the legs. The opposite movement of hip flexion is hip extension. The sartorius can flex the hip joint.

This image shows an example of hip abduction, which involves moving the leg out to the side (laterally). The opposite of hip abduction is hip adduction. The sartorius can abduct the hip joint.

This image depicts an example of hip external rotation, which involves rotating the leg from the hip joint outwards (laterally). External rotation is also referred to as lateral rotation. The opposite of external rotation (lateral rotation) is internal rotation (medial rotation). The sartorius can externally rotate the hip joint.

In this image, you can see an example of medial rotation of the tibia. Medial rotation of the tibia involves inward rotation of the shinbone towards the midline of the body. The opposite movement of medial rotation of the tibia is lateral rotation of the tibia. The sartorius can medially rotate the tibia when the knee is flexed.

Innervation

The sartorius muscle is innervated by the anterior division of the femoral nerve, which arises from the second, third, and fourth lumbar spinal nerves (L2, L3, L4). These nerves emerge from the lumbar section of the spinal cord, which is located in the lower back. These nerves are part of the larger lumbosacral plexus, a network of intersecting nerves that provide motor and sensory functions to the lower body [24] [25].

The femoral nerve, the largest branch of the lumbar plexus, originates from the dorsal divisions of the second, third, and fourth lumbar nerves (L2, L3, L4). The nerve descends posteriorly to the psoas major, running between this muscle and the iliacus. It then passes beneath the inguinal ligament, a band of connective tissue that runs from the hip to the pubic bone, and enters the femoral triangle, an area in the upper thigh [26] [27].

Within the femoral triangle, the femoral nerve splits into two main divisions: anterior and posterior. The anterior division, from which the sartorius muscle receives its innervation, also provides nerve supply to the pectineus and iliacus muscles. The posterior division primarily innervates the quadriceps muscle group, which includes the rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, and vastus intermedius [28] [29].

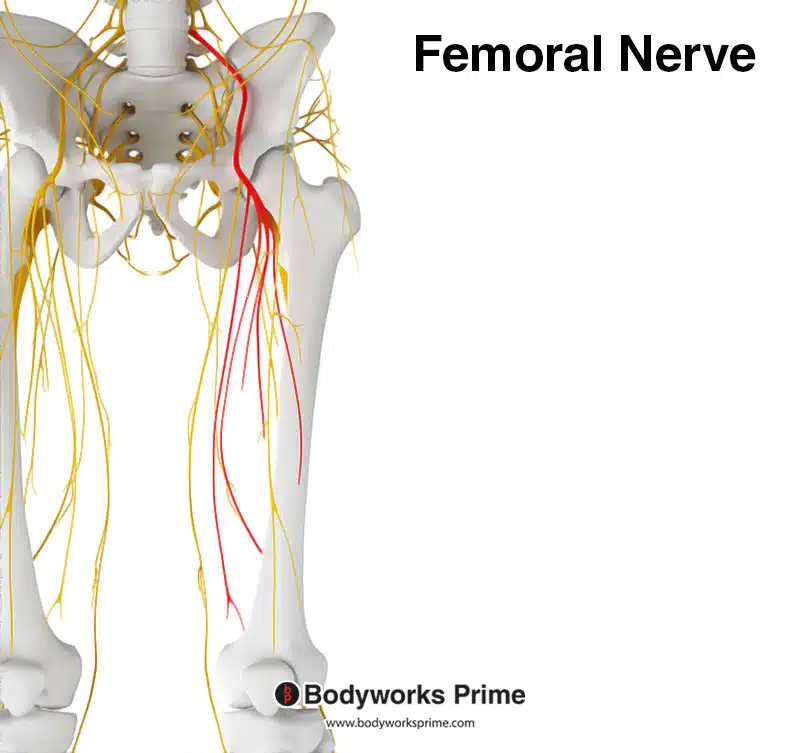

Here we can see the femoral nerve highlighted in red. The femoral nerve’s anterior division innervates the sartorius muscle from the spinal nerve roots of L2, L3, and L4.

Blood Supply

The primary blood supply to the sartorius muscle originates from the muscular branches of the femoral artery, which is a direct continuation of the external iliac artery after it crosses the inguinal ligament [30] [31]. The femoral artery provides more than half of the blood supply to the sartorius muscle [32].

In addition to the femoral artery, the sartorius receives collateral blood flow from various other arteries. The proximal part of the sartorius muscle receives some of its supply from the superficial circumflex iliac artery, a branch of the femoral artery that primarily supplies the skin over the inguinal ligament and the upper part of the thigh. Another source of collateral blood supply, particularly to the middle part of the sartorius, is the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery. This artery mainly supplies the vastus lateralis and rectus femoris muscles [33].

The distal portion of the sartorius muscle receives collateral blood supply from the descending genicular artery and the superior medial genicular artery, both of which predominantly supply the knee joint and muscles in its vicinity [34].

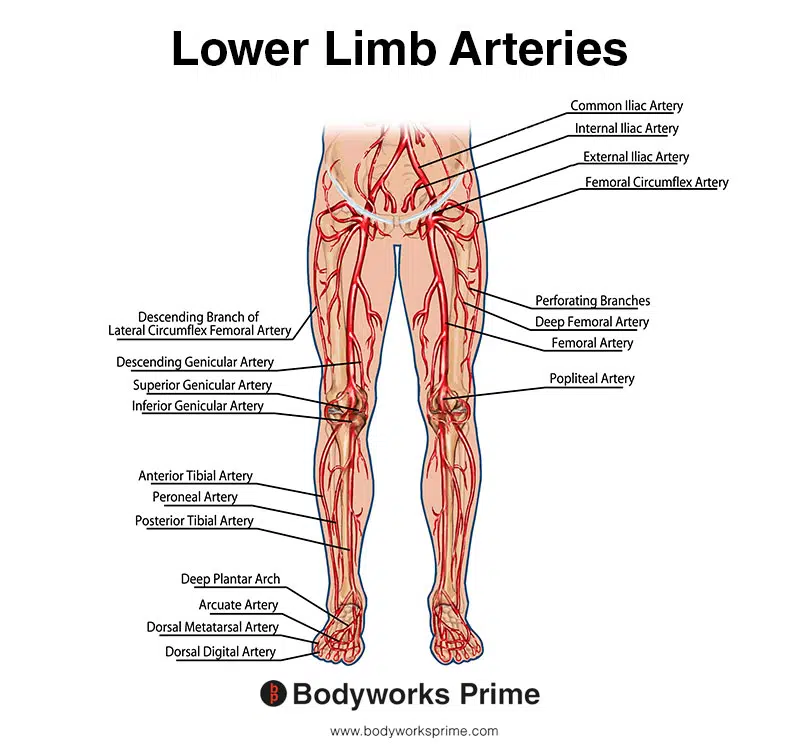

This image shows the arteries of the lower limb, including the femoral artery.

Want some flashcards to help you remember this information? Then click the link below:

sartorius muscle flashcards

Support Bodyworks Prime

Running a website and YouTube channel can be expensive. Your donation helps support the creation of more content for my website and YouTube channel. All donation proceeds go towards covering expenses only. Every contribution, big or small, makes a difference!

References

| ↑1, ↑8, ↑17, ↑18, ↑20, ↑22, ↑23, ↑24, ↑26, ↑28, ↑32, ↑33, ↑34 | Walters BB, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Sartorius Muscle. [Updated 2022 Aug 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532889/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑6, ↑9, ↑11, ↑13, ↑15, ↑25, ↑27, ↑29 | Standring S. (2015). Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st Edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier. |

| ↑3, ↑7, ↑12, ↑31 | Moore KL, Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2017. |

| ↑4, ↑5, ↑10 | Khan A, Arain A. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Anterior Thigh Muscles. [Updated 2023 Mar 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538425/ |

| ↑14 | Mohseni M, Graham C. Pes Anserine Bursitis. [Updated 2021 Jul 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532941/ |

| ↑16, ↑19, ↑21 | Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the hip: a focus on muscular actions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010 Feb;40(2):82-94. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3025. PMID: 20118525. |

| ↑30 | Arias DG, Marappa-Ganeshan R. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Arteries. [Updated 2022 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544319/ |