| Origin | Direct head: anterior aspect of the inferior iliac spine Indirect head: acetabular ridge |

| Insertion | Patellar ligament which inserts onto the tibial tuberosity |

| Action | Extends the knee Flexes the hip |

| Nerve | Femoral nerve (L2, L3, L4) |

| Artery | Femoral artery |

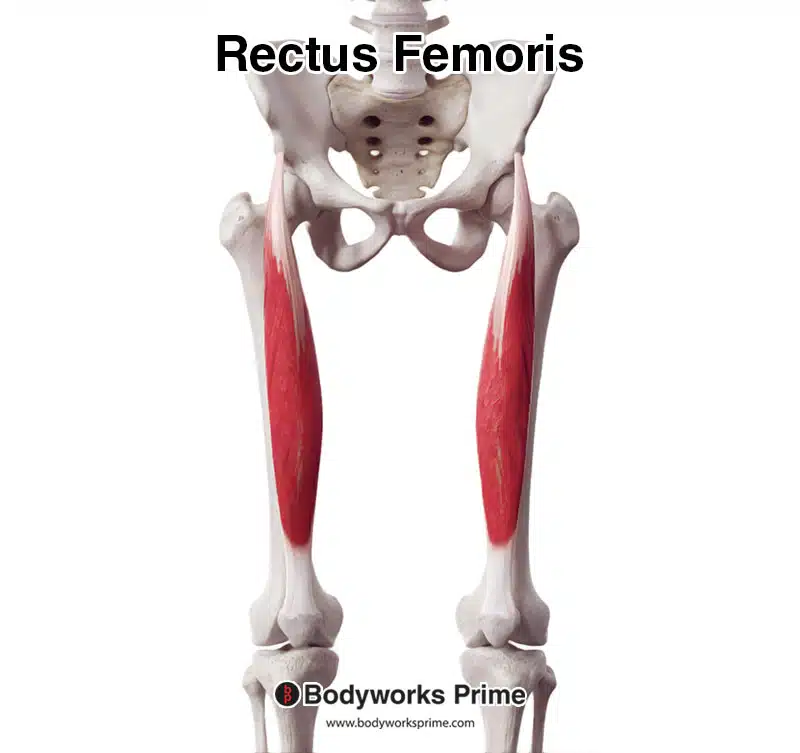

Location & Overview

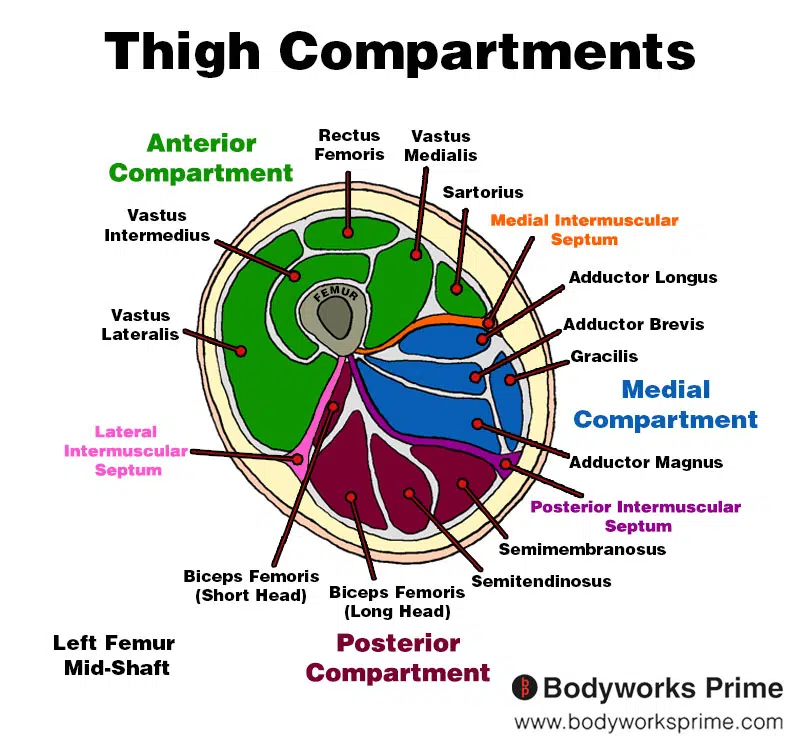

The rectus femoris is a large, superficial muscle located in the anterior compartment of the thigh, forming a significant part of the quadriceps muscle group. The other quadricep muscles include: the vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and the vastus lateralis. These four muscles collectively contribute to knee extension and, to some extent, hip flexion. The rectus femoris is unique among the quadriceps muscles because it crosses both the hip and knee joints, making it the only quadriceps muscle involved in both actions. The fibers of all four quadriceps muscles converge into a single quadriceps tendon, which attaches to the patella [1] [2].

The rectus femoris is a bi-articular muscle, which means it has the ability to act on two joints simultaneously. This characteristic allows for a more efficient transfer of forces between the hip and knee joints, contributing to coordinated lower limb movements during various activities, such as walking, running, and jumping [3].

Exercises that specifically target the rectus femoris should emphasize both hip flexion and knee extension, either concurrently or separately, as the rectus femoris spans both the knee and hip joints. One such exercise that combines both hip flexion and knee extension simultaneously is the Bulgarian split squat. This exercise engages the rectus femoris by incorporating hip flexion and knee extension while promoting greater muscle elongation in the posterior leg [4]. Walking lunges have a similar effect on stretching the rectus femoris in the posterior leg, albeit to a lesser extent, as the hip is less extended compared to the Bulgarian split squat [5].

Conventional compound exercises like squats and leg presses also activate the rectus femoris, but at a more shortened muscle length than Bulgarian split squats and lunges [6]. Neglecting to include any rectus femoris training at extended muscle lengths in one’s program may lead to suboptimal muscle development.

Here we can see the rectus femoris in isolation from an anterior view.

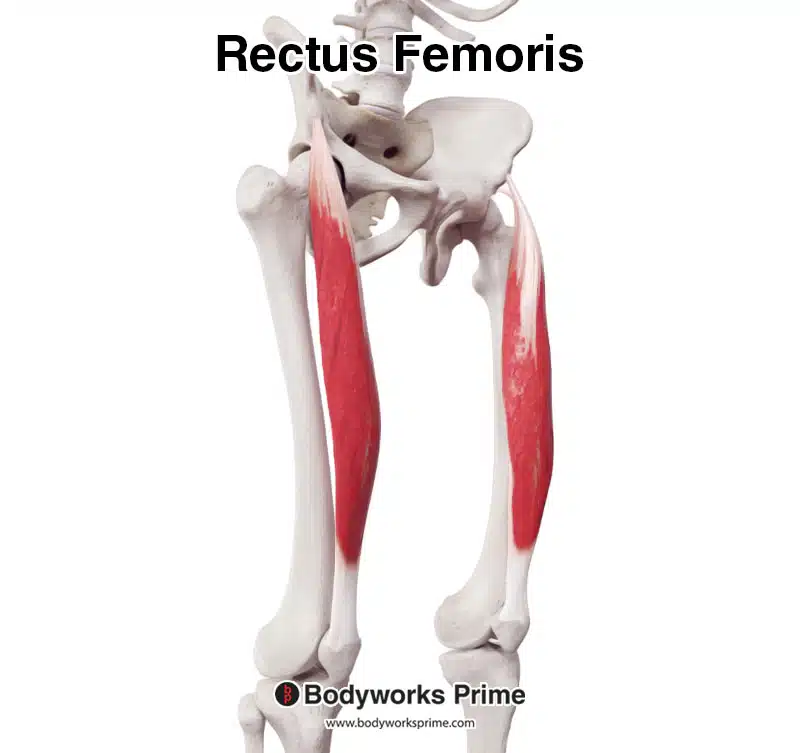

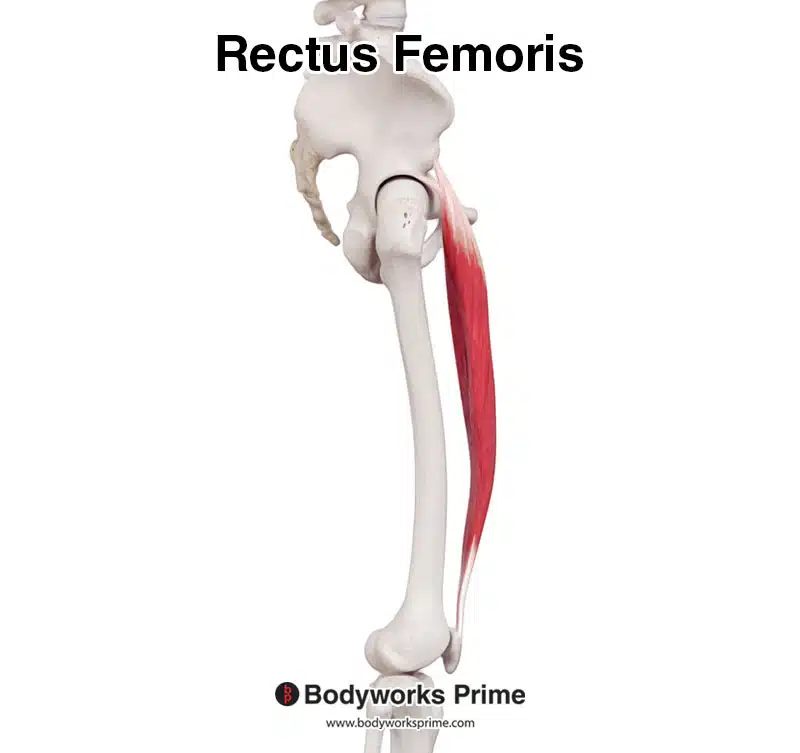

Here we can see the rectus femoris in isolation from an anterolateral view.

Here we can see the rectus femoris muscle from a lateral view.

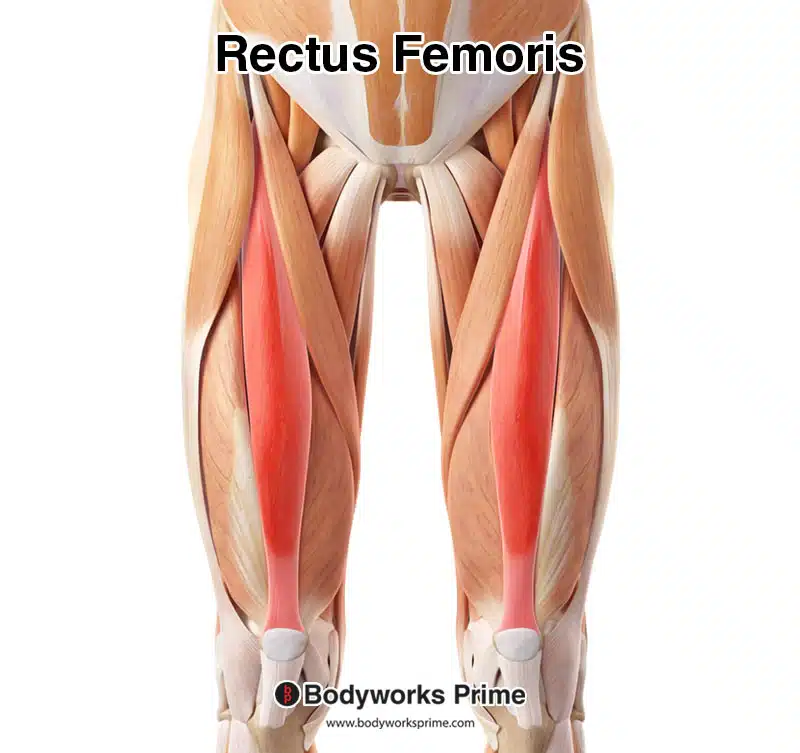

Pictured here is the rectus femoris highlighted in red, seen from an anterior view, amongst the other muscles of the leg.

Here we can see an image of the compartments of the thigh. We can see the rectus femoris in the anterior compartment, the section coloured in green.

Origin & Insertion

The rectus femoris muscle is unique among the quadriceps muscles, as it has two heads of origin: the direct (straight) head and the indirect (reflected) head. The direct head originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS), while the indirect head arises from the superior part of the acetabulum, on the acetabular ridge or the ilium just above the acetabulum (the acetabulum is the the ‘ball-and-socket’ joint the hip sits in) [7] [8] [9]. These two heads merge to form the main muscle belly [10].

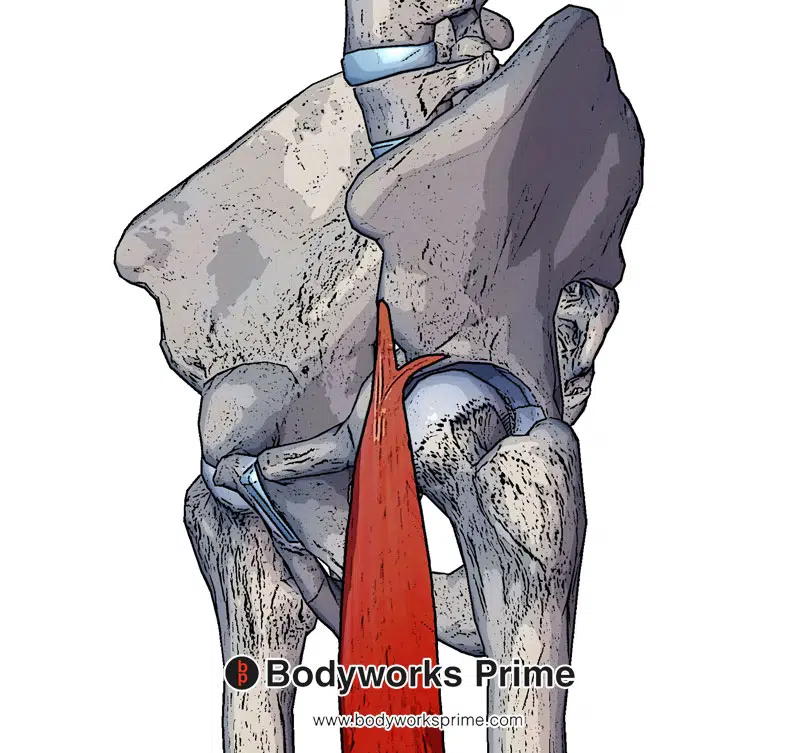

As the rectus femoris descends down the leg, it converges with the other three quadriceps muscles (vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis) to form the quadriceps tendon. This tendon’s fibers travel superficial to the patella and continue distally, as the patellar ligament. The patellar ligament inserts onto the tibial tuberosity [11] [12].

Anatomical variations in the origins of the rectus femoris have been reported, though they are relatively rare. In some cases, the muscle may have additional heads or slips originating from the ilium or the capsule of the hip joint [13] [14] [15]

.

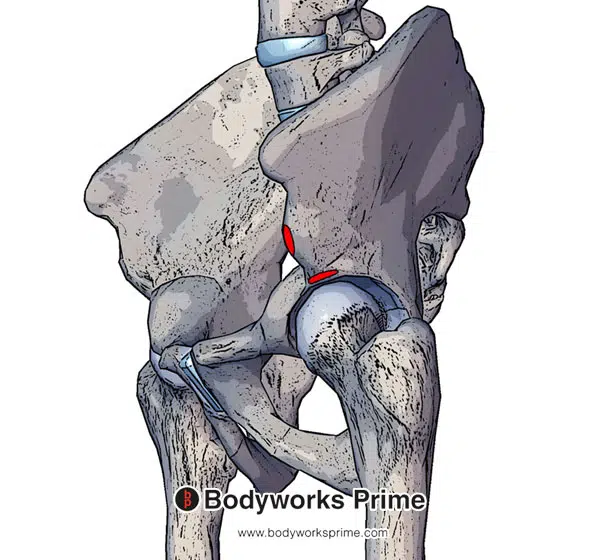

Here we can see the two heads of origin of the rectus femoris. The direct head (originating at the anterior aspect of the inferior iliac spine) and the indirect head (originating at the acetabular ridge).

Here we can see the origins of the rectus femoris muscle. The direct head originates at the anterior aspect of the inferior iliac spine and the indirect head originates at the acetabular ridge.

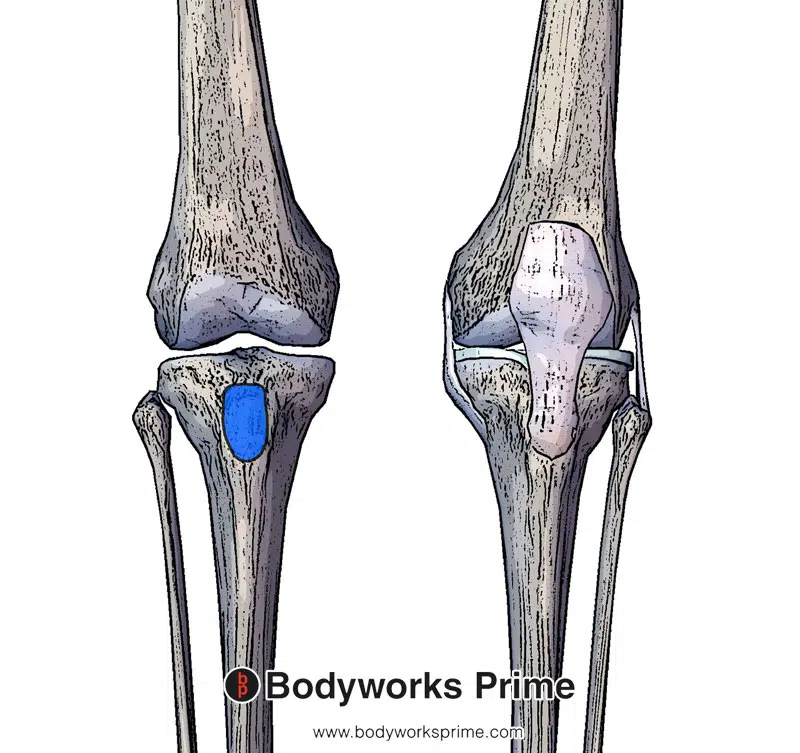

Here we can see the insertion of the patellar ligament on the tibial tuberosity. The rectus femoris inserts into the patellar ligament.

Actions

The rectus femoris is a biarticular muscle, meaning it crosses two joints: the hip and the knee. Due to this, the rectus femoris plays a dual role in the movement of these joints [16] [17] [18].

The primary action of the rectus femoris at the knee joint is knee extension. As a part of the quadriceps muscle group, it works synergistically with the vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis to extend the knee, especially during activities like walking, running, jumping, and squatting [19] [20] [21].

At the hip joint, the rectus femoris acts as a hip flexor, working in conjunction with other muscles such as the iliopsoas and sartorius to flex the hip. This action is particularly important during the swing phase of gait, as well as during activities that require hip flexion, such as sprinting and walking up stairs [22] [23] [24].

Due to its dual role in both hip flexion and knee extension, the rectus femoris functions as an antagonist to the hamstring muscles at both the hip and knee joints. The hamstrings are primarily responsible for hip extension and knee flexion, so their actions oppose those of the rectus femoris [25] [26].

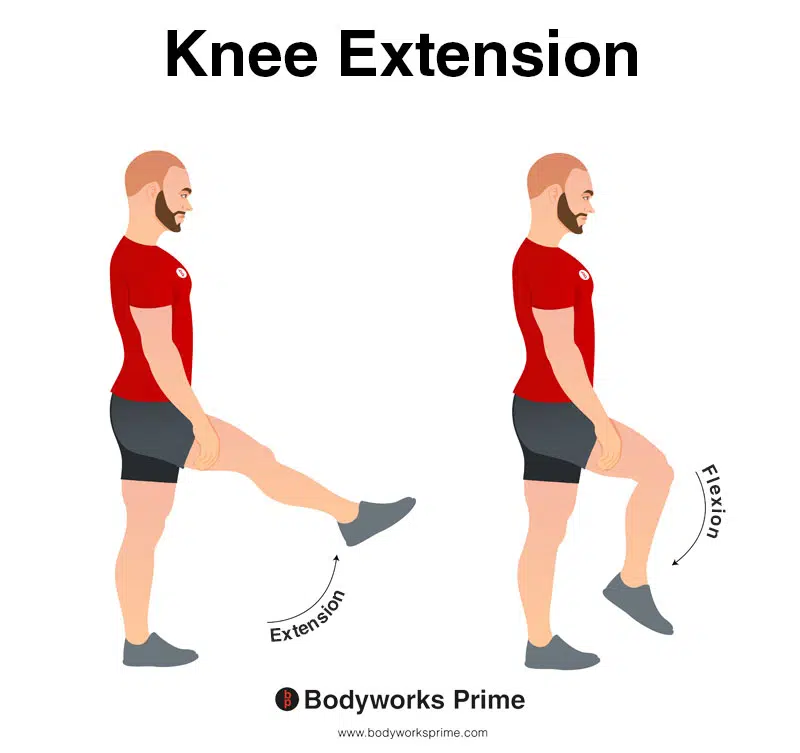

In this image, you can see an example of knee extension, which is the action of straightening out your leg at the knee. The opposite movement of knee flexion is knee extension. The primary role of the rectus femoris is knee flexion.

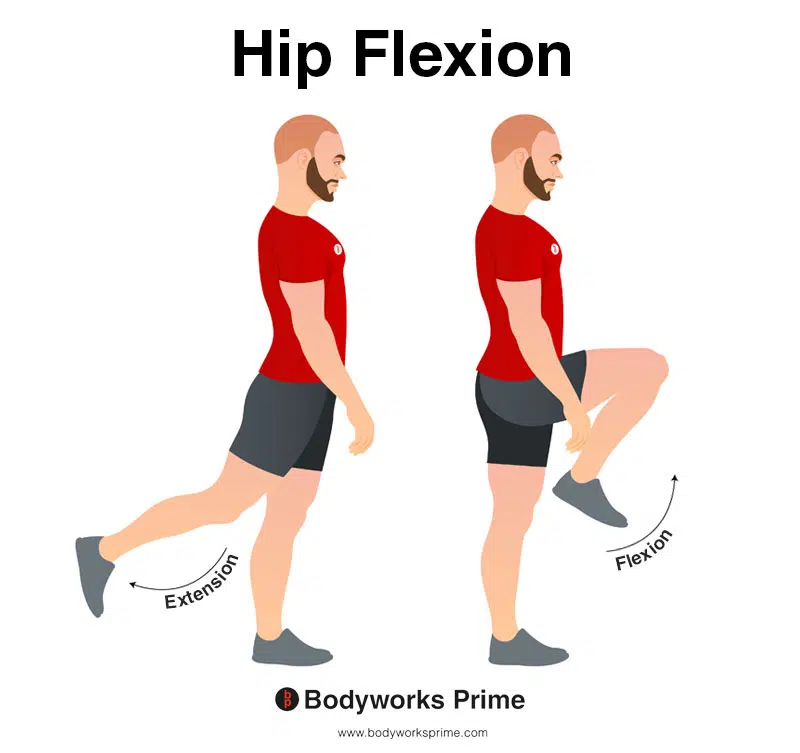

In this image, you can see an example of hip flexion, which is the action of raising your leg up in front of you and causing your hip to bend. If both legs are fixed, the torso will lean forward towards the legs. The opposite movement of hip flexion is hip extension. A secondary role of the rectus femoris is hip flexion.

Innervation

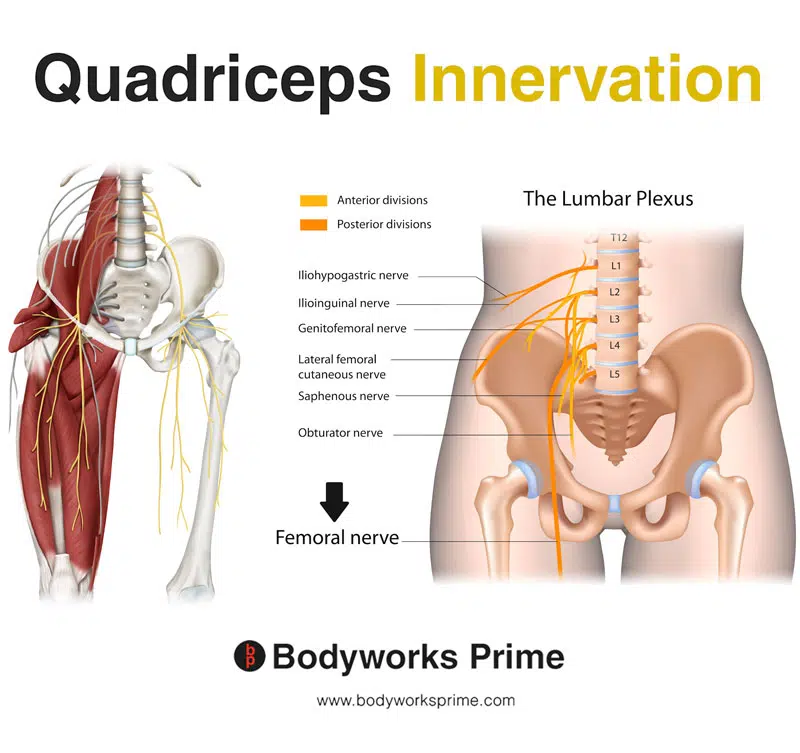

The innervation of the rectus femoris muscle is provided by the femoral nerve, a nerve that originates from the lumbar plexus and is composed of fibers from the L2, L3, and L4 spinal nerve roots. Apart from the rectus femoris, the femoral nerve also innervates the remaining quadriceps muscles: vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis [27] [28].

The femoral nerve plays a vital role in transmitting motor commands from the spinal cord to the rectus femoris, allowing for the execution of movements such as knee extension and hip flexion. Furthermore, the nerve is responsible for transmitting sensory information from the skin and deeper structures of the anterior thigh and medial leg back to the central nervous system [29] [30].

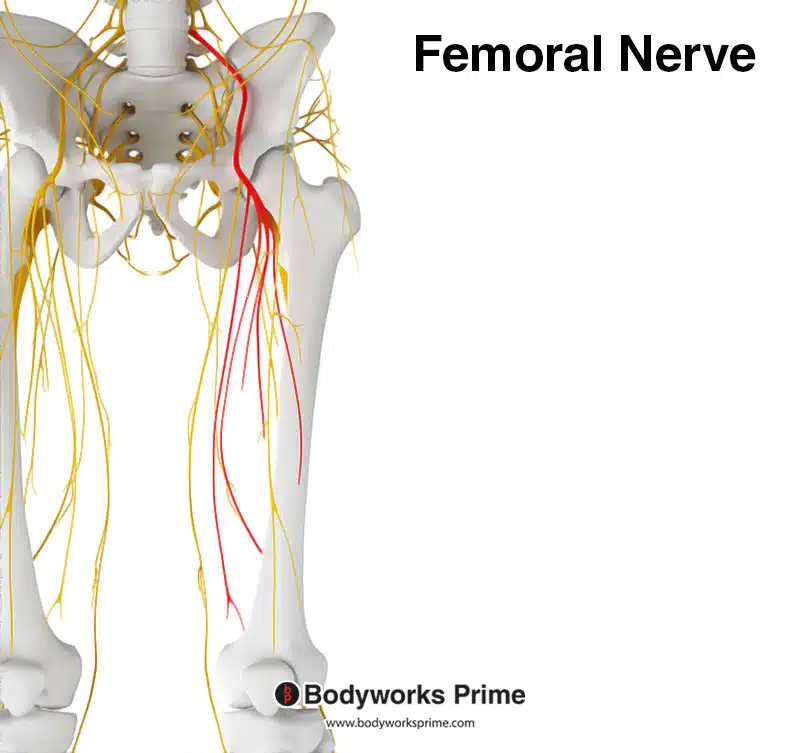

Here we can see the femoral nerve highlighted in red. The femoral nerve innervates the quadriceps muscle group, including the rectus femoris. The femoral nerve originates from the spinal nerve roots of L2, L3, and L4.

Here we can see the innervation of the quadriceps muscle group, the femoral nerve is a major branch of the lumbar plexus.

Blood Supply

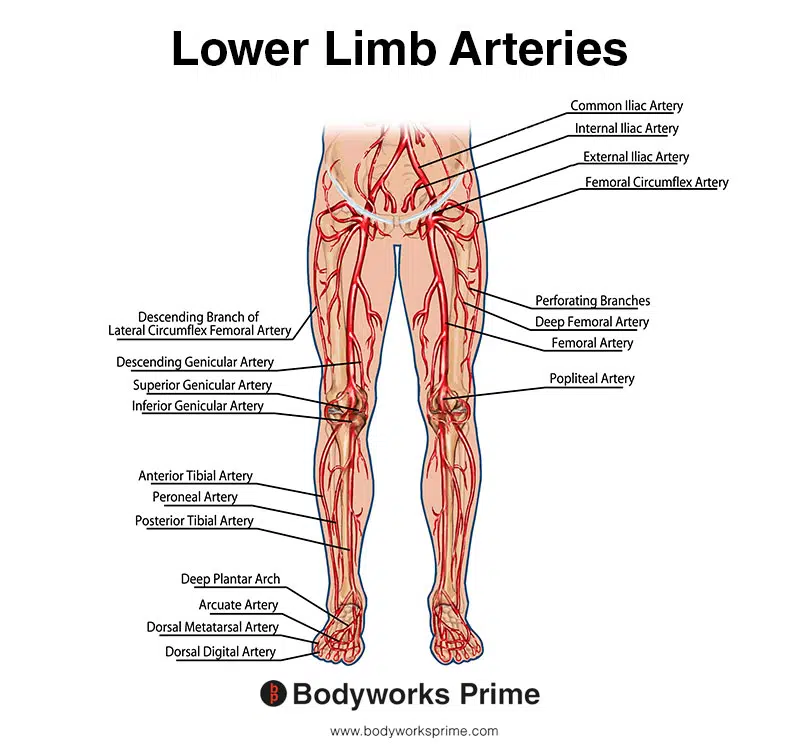

Blood is supplied to the rectus femoris from the femoral artery. The other three quadricep muscles (vastus medialis, vastus intermedius and the vastus lateralis) also get their blood supply from the femoral artery [31].

This image shows the arteries of the lower limb, including the femoral artery.

Want some flashcards to help you remember this information? Then click the link below:

Rectus Femoris Flashcards

Support Bodyworks Prime

Running a website and YouTube channel can be expensive. Your donation helps support the creation of more content for my website and YouTube channel. All donation proceeds go towards covering expenses only. Every contribution, big or small, makes a difference!

References

| ↑1, ↑8, ↑11, ↑16, ↑19, ↑22, ↑25, ↑27, ↑29 | Murdock CJ, Mudreac A, Agyeman K. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Rectus Femoris Muscle. [Updated 2022 Nov 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539897/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑9 | Standring S. (2015). Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st Edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier. |

| ↑3, ↑17 | Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017. |

| ↑4 | Bloomquist K, Langberg H, Karlsen S, Madsgaard S, Boesen M, Raastad T. Effect of range of motion in heavy load squatting on muscle and tendon adaptations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013 Aug;113(8):2133-42. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2642-7. Epub 2013 Apr 20. PMID: 23604798. |

| ↑5 | Farrokhi S, Pollard CD, Souza RB, Chen YJ, Reischl S, Powers CM. Trunk position influences the kinematics, kinetics, and muscle activity of the lead lower extremity during the forward lunge exercise. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008 Jul;38(7):403-9. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2634. Epub 2008 Apr 15. PMID: 18591759. |

| ↑6 | Escamilla RF, Fleisig GS, Zheng N, Barrentine SW, Wilk KE, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of the knee during closed kinetic chain and open kinetic chain exercises. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998 Apr;30(4):556-69. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199804000-00014. PMID: 9565938. |

| ↑7 | Kumaravel M, Bawa P, Murai N. Magnetic resonance imaging of muscle injury in elite American football players: Predictors for return to play and performance. Eur J Radiol. 2018 Nov;108:155-164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.09.028. Epub 2018 Sep 27. PMID: 30396649. |

| ↑10, ↑28, ↑30 | Moore KL, Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2017. |

| ↑12, ↑18, ↑21, ↑24, ↑31 | Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Thigh Quadriceps Muscle. 2021 Jul 22. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 30020706. |

| ↑13 | Tubbs RS, Stetler W Jr, Savage AJ, Shoja MM, Shakeri AB, Loukas M, Salter EG, Oakes WJ. Does a third head of the rectus femoris muscle exist? Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2006 Nov;65(4):377-80. PMID: 17171618. |

| ↑14 | Duda GN, Brand D, Freitag S, Lierse W, Schneider E. Variability of femoral muscle attachments. J Biomech. 1996 Sep;29(9):1185-90. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)00025-5. PMID: 8872275. |

| ↑15 | Moore VA, Xu L, Olewnik Ł, Georgiev GP, Iwanaga J, Tubbs RS. Previously unreported variant of the rectus femoris muscle. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2023;82(1):221-224. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2022.0010. Epub 2022 Feb 3. PMID: 35112338. |

| ↑20 | Escamilla RF, Fleisig GS, Zheng N, Lander JE, Barrentine SW, Andrews JR, Bergemann BW, Moorman CT 3rd. Effects of technique variations on knee biomechanics during the squat and leg press. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 Sep;33(9):1552-66. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200109000-00020. PMID: 11528346. |

| ↑23 | Sahrmann S, Azevedo DC, Dillen LV. Diagnosis and treatment of movement system impairment syndromes. Braz J Phys Ther. 2017 Nov-Dec;21(6):391-399. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2017.08.001. Epub 2017 Sep 27. PMID: 29097026; PMCID: PMC5693453. |

| ↑26 | Chumanov ES, Heiderscheit BC, Thelen DG. Hamstring musculotendon dynamics during stance and swing phases of high-speed running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Mar;43(3):525-32. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181f23fe8. PMID: 20689454; PMCID: PMC3057086. |