| Origin | Ischial tuberosity |

| Insertion | Medial surface of superior tibia |

| Action | Flexes knee Extends the hip Medially rotates the tibia when knee is flexed |

| Nerve | Sciatic (tibial, L5, S1, S2) |

| Artery | Inferior gluteal artery Perforating arteries |

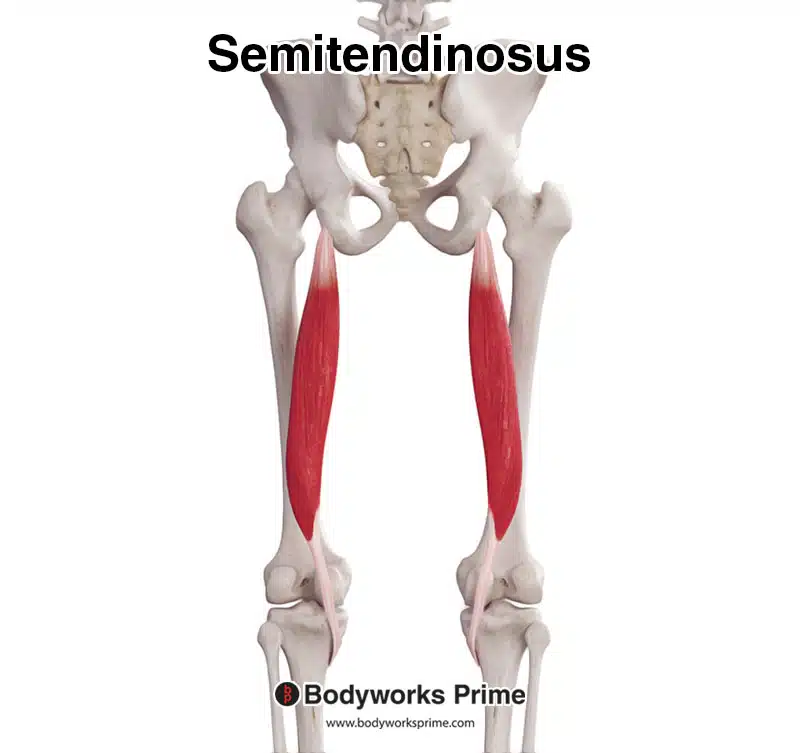

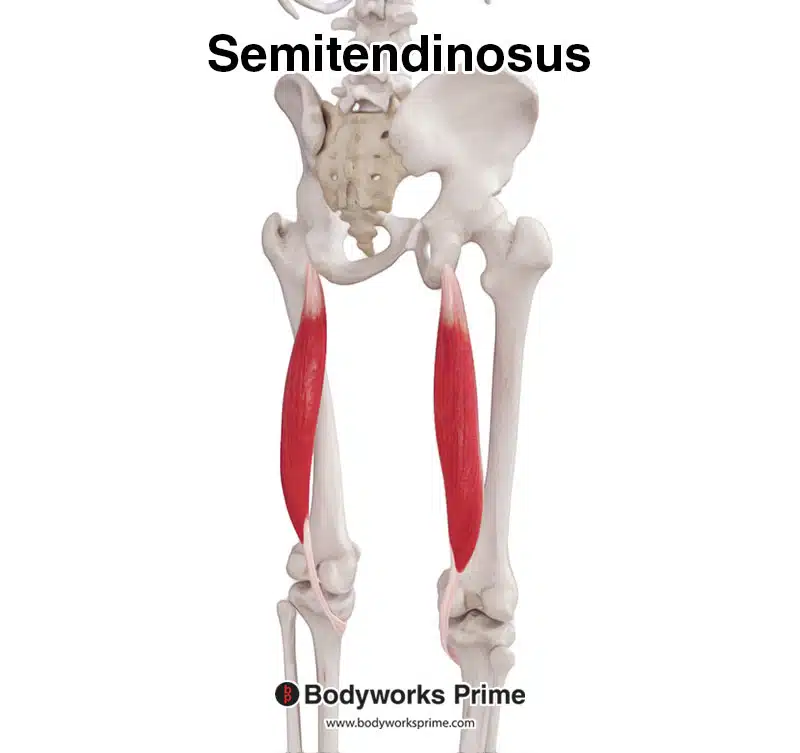

Location & Overview

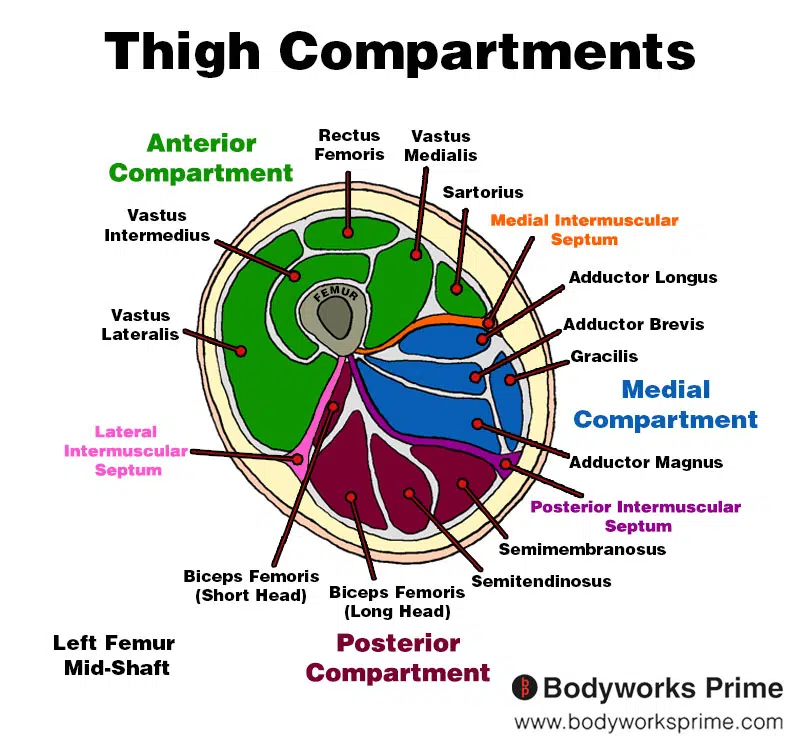

The semitendinosus muscle is one of the three muscles that make up the hamstring muscle group. The other two hamstring muscle are: the semimembranosus and biceps femoris muscles. The semitendinosus is the most centrally located hamstring muscle. It is located in the posterior compartment of the thigh, between the biceps femoris and semimembranosus. The semitendinosus muscle is more superficial than the semimembranosus (meaning it is located closer to the skin’s surface) and the semitendinosus covers up a large portion of the semimembranosus. The semitendinosus’ attachments are relatively close to those of the semimembranosus, which shows their close anatomical relationship [1].

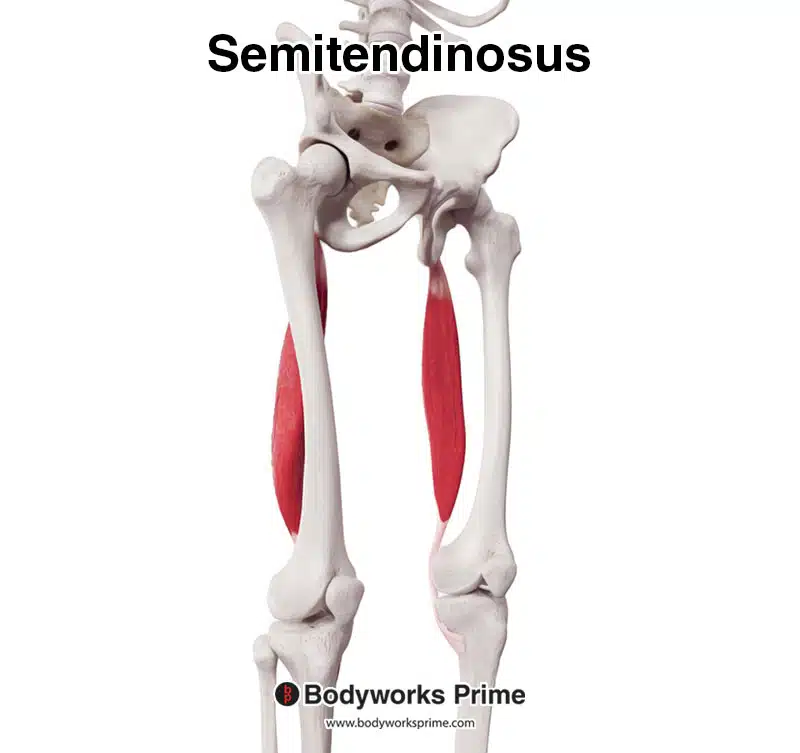

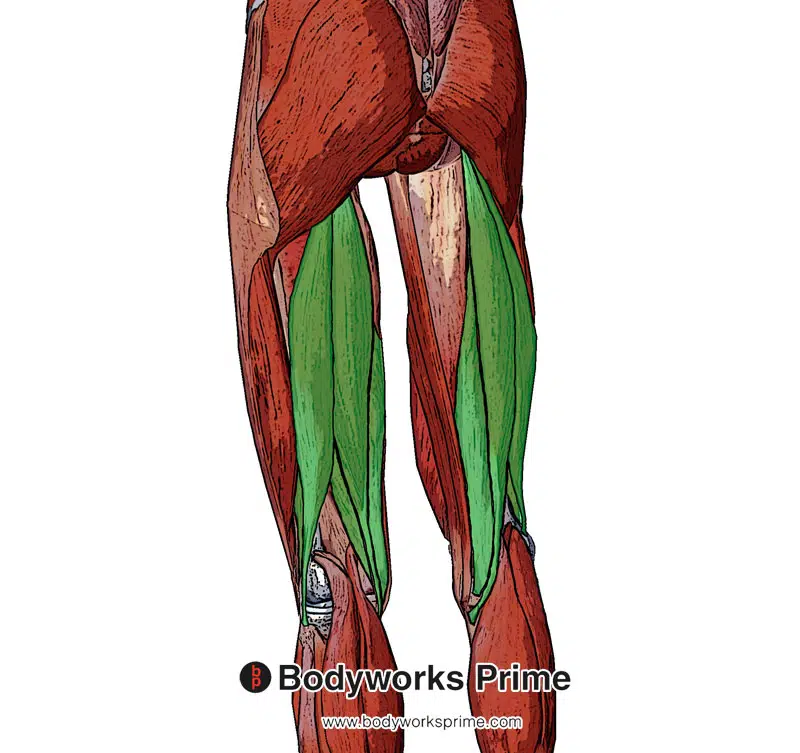

Here we can see the semitendinosus muscle from a posterior view.

Here we can see the semitendinosus muscle from a posterolateral view.

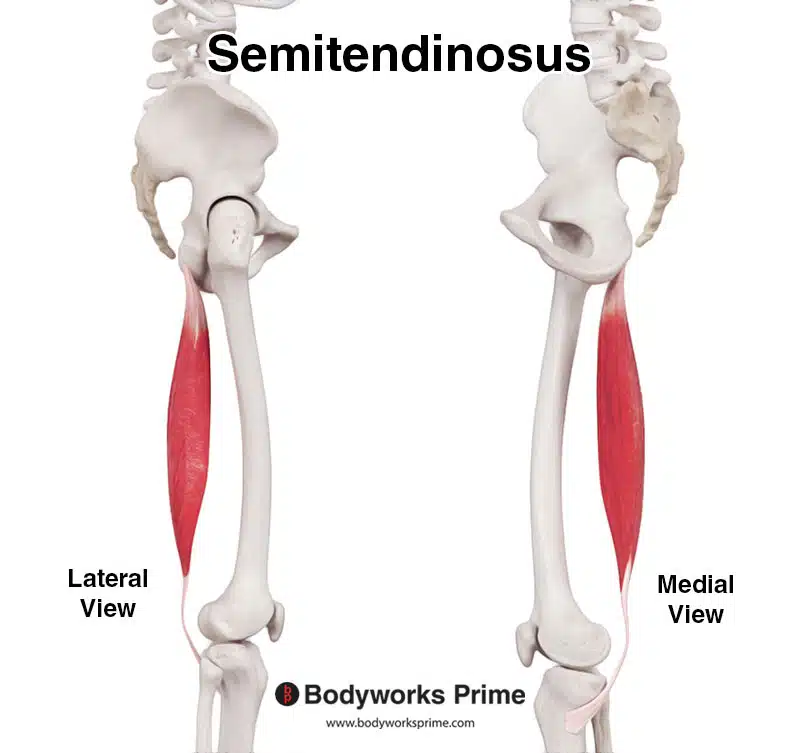

Here we can see the semitendinosus muscle from a lateral and medial view. The lateral view is on the left and the medial view is on the right.

Here we can see the semitendinosus muscle from a anterolateral view.

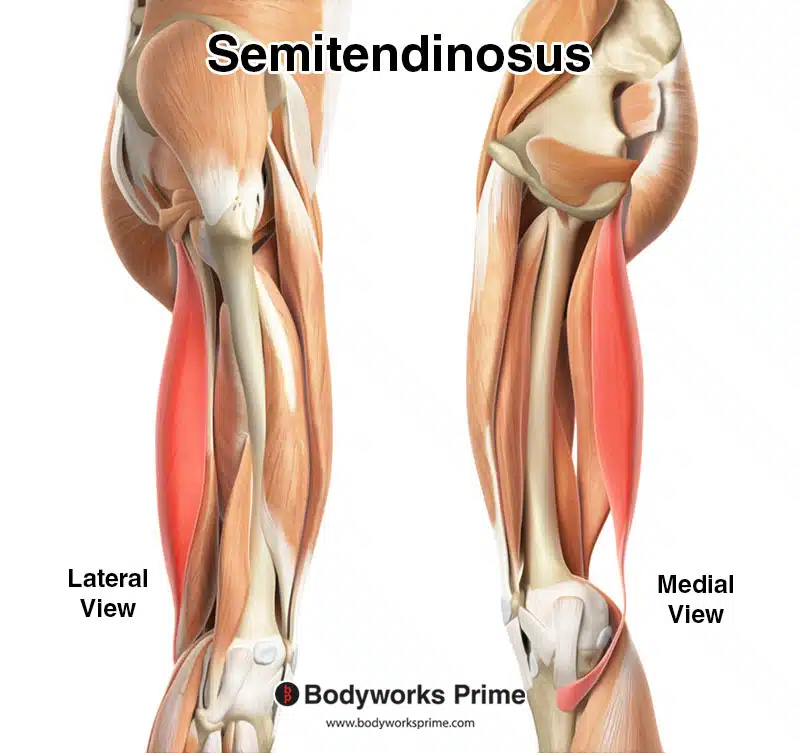

Here we can see the semitendinosus muscle highlighted in red amongst the other muscles of the hip and thigh, seen from a lateral and medial view. The lateral view is on the left and the medial view is on the right.

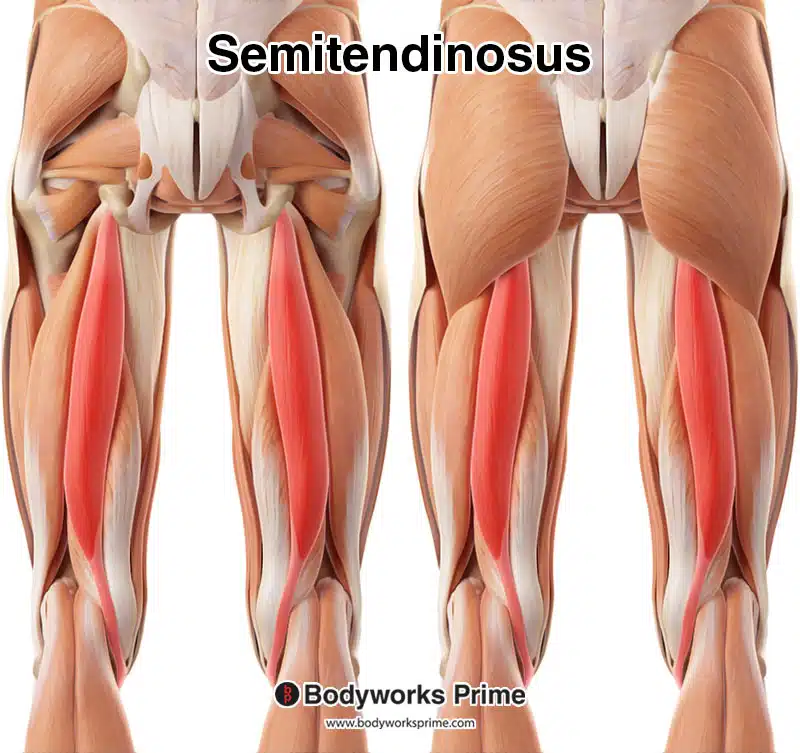

Here we can see the semitendinosus muscle highlighted in red amongst the other muscles of the hip and thigh, seen from a posterior view. The gluteus maximus muscle is removed from the left side of the image to show its position in relation to this muscle.

Here we can see the semitendinosus muscle and the rest of the hamstring muscles from a superficial view.

Here we can see an image of the compartments of the thigh. We can see the semitendinosus in the posterior compartment, the section coloured in red.

Origin & Insertion

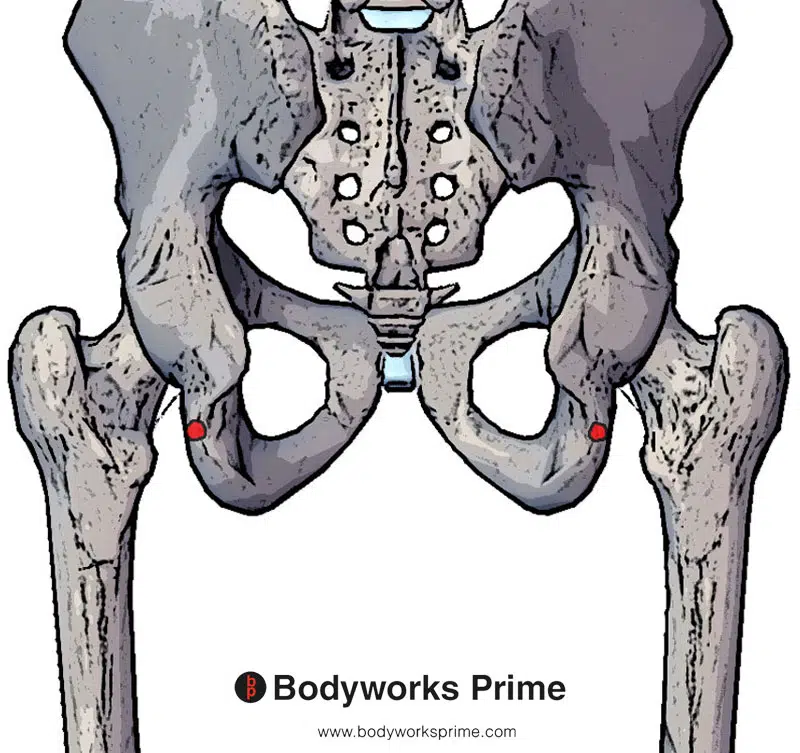

The semitendinosus originates at the superior portion of the ischial tuberosity. The ischial tuberosity is bony protrusion located on the posterior aspect of the ischium, which is the lower part of the hip bone. This origin point is shared with the other two hamstring muscles (semimembranosus and semitendinosus) [2] [3].

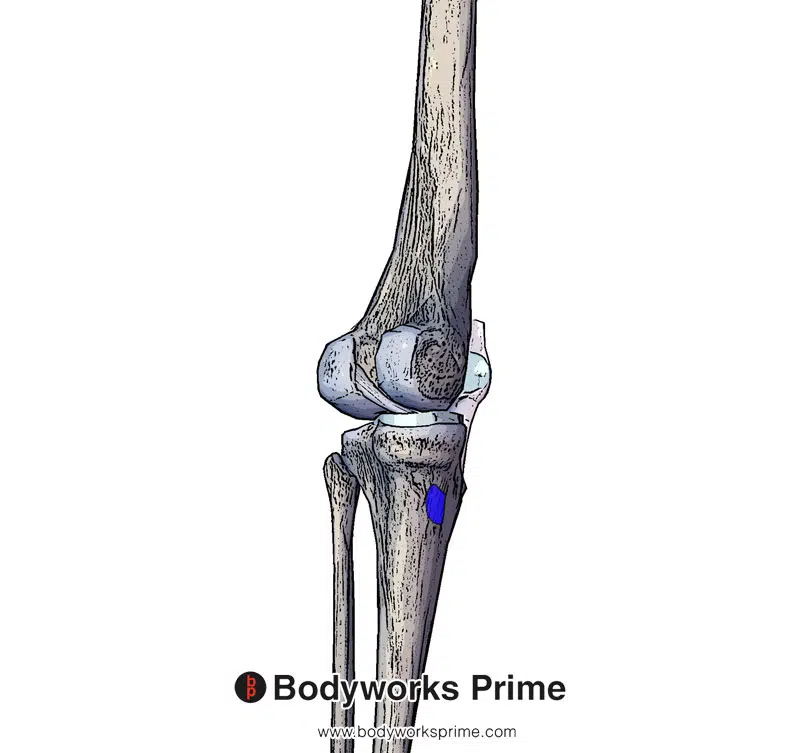

The muscle then works its way down the posterior and medial portion of the thigh, where it then inserts below the knee joint, on the medial surface of the superior part of the tibia. This insertion is part of the group of tendons called the ‘pes anserinus’ which insert in this region. This insertion is part of the group of tendons known as the ‘pes anserinus,’ which includes the tendons of the semitendinosus, sartorius, and gracilis muscles [4] [5].

Here we can see the origin of the semitendinosus muscle highlighted in red. It originates at the ischial tuberosity.

Here we can see the insertion of the semitendinosus muscle highlighted in blue. It inserts at the medial surface of superior tibia.

Actions & Function

The semitendinosus muscle plays a role in several movements at the hip and knee joints. Its primary functions include flexing the knee joint, extending the hip joint, and medially rotating the tibia on the femur when the knee is flexed [6] [7].

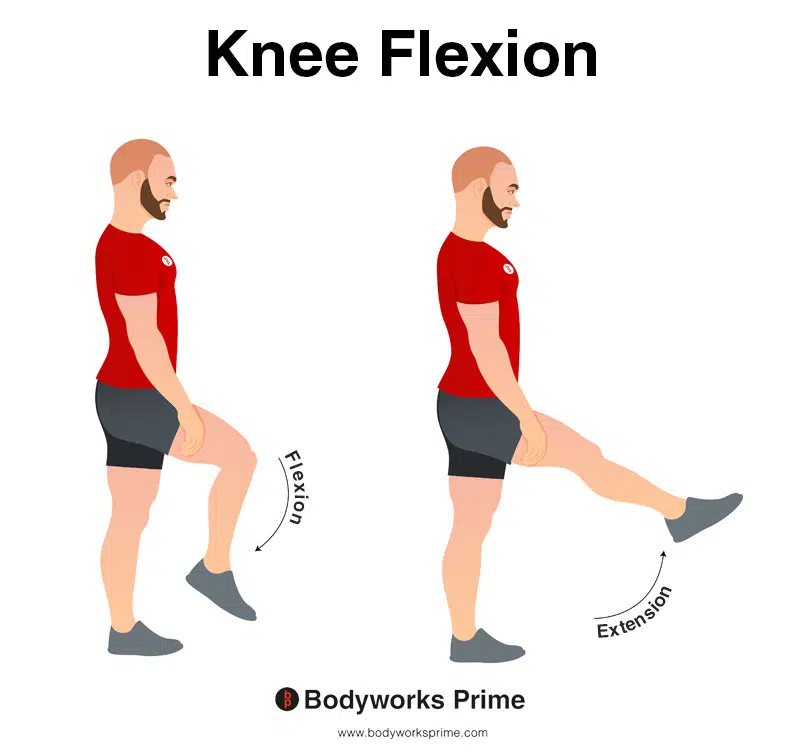

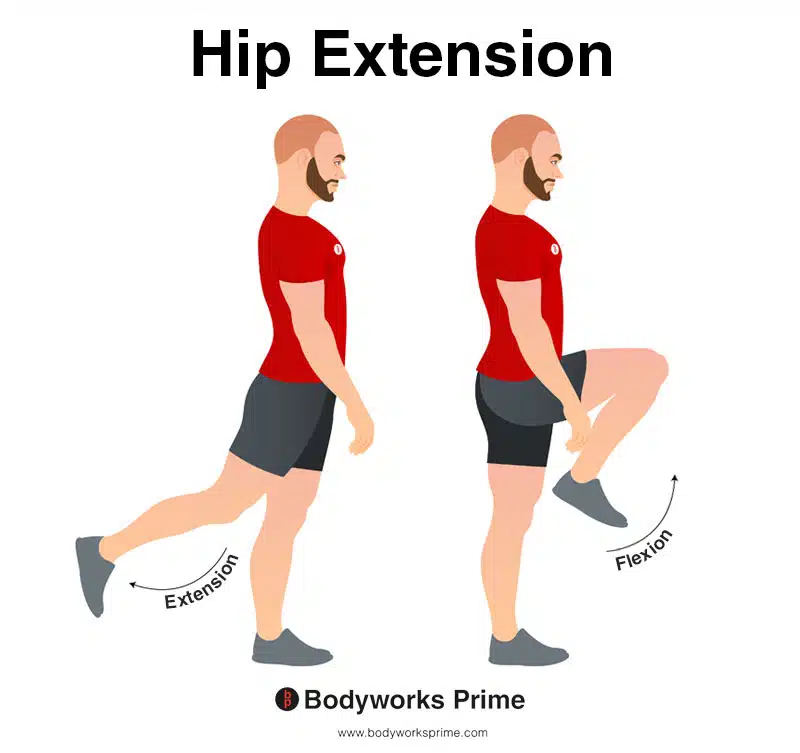

Flexion of the knee joint involves bending the knee, which brings the lower leg closer to the back of the thigh. Extension of the hip joint involves moving the thigh backward relative to the hip, such as when pushing off the ground when walking [8] [9].

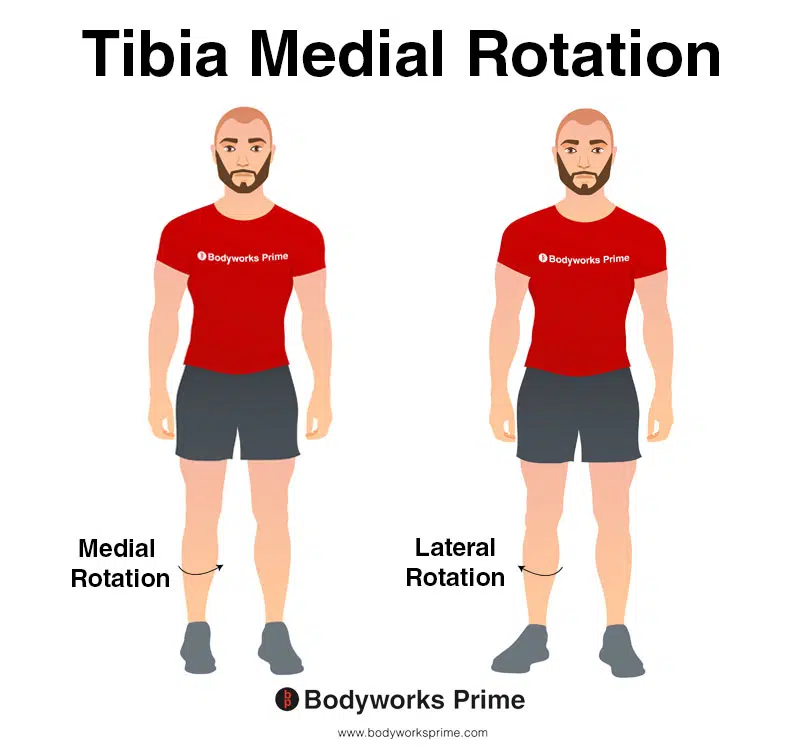

Furthermore, the semitendinosus muscle assists in medially (internally) rotating the tibia on the femur when the knee is flexed. This action involves turning the lower leg (tibia) inward relative to the thigh, but without moving the thigh itself [10] [11].

In this image, you can see an example of knee flexion, which is the action of bending your knee. The opposite movement of knee flexion is knee extension. The semitendinosus contributes to flexion of the knee joint.

In this image, you can see an example of hip extension. Hip extension is the movement of the thigh or the upper leg backward, away from the body, in the sagittal plane. This action involves increasing the angle between the thigh and the pelvis, causing the hip joint to straighten or extend. The opposite movement of hip extension is hip flexion. The semitendinosus contributes to extension of the hip joint.

In this image, you can see an example of medial rotation of the tibia. Medial rotation of the tibia involves inward rotation of the shinbone towards the midline of the body. The opposite movement of medial rotation of the tibia is lateral rotation of the tibia. The semitendinosus contributes to lateral rotation of the tibia when the knee is flexed.

Innervation

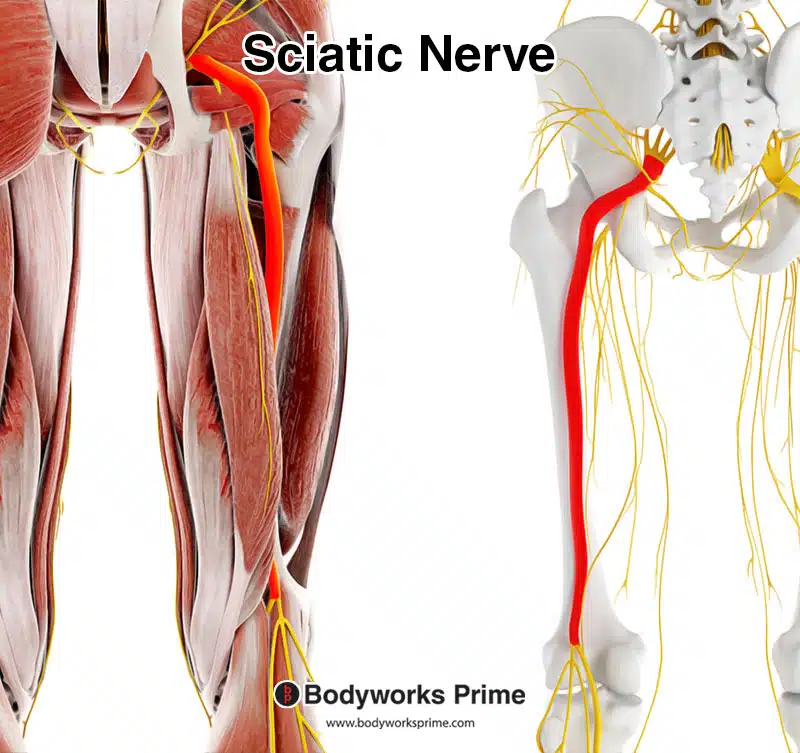

The semitendinosus muscle receives its innervation from the tibial division of the sciatic nerve, which comes from nerve roots L5, S1, and S2 [12]. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body and provides motor and sensory functions to the lower limbs [13].

The tibial division of the sciatic nerve supplies the motor signals necessary for the semitendinosus muscle to perform its actions, such as flexing the knee, extending the hip, and medially rotating the tibia on the femur when the knee is flexed [14]. In addition, the sciatic nerve also carries sensory information from the skin and deeper structures of the lower limb, enabling for the perception of touch, pain, and temperature [15].

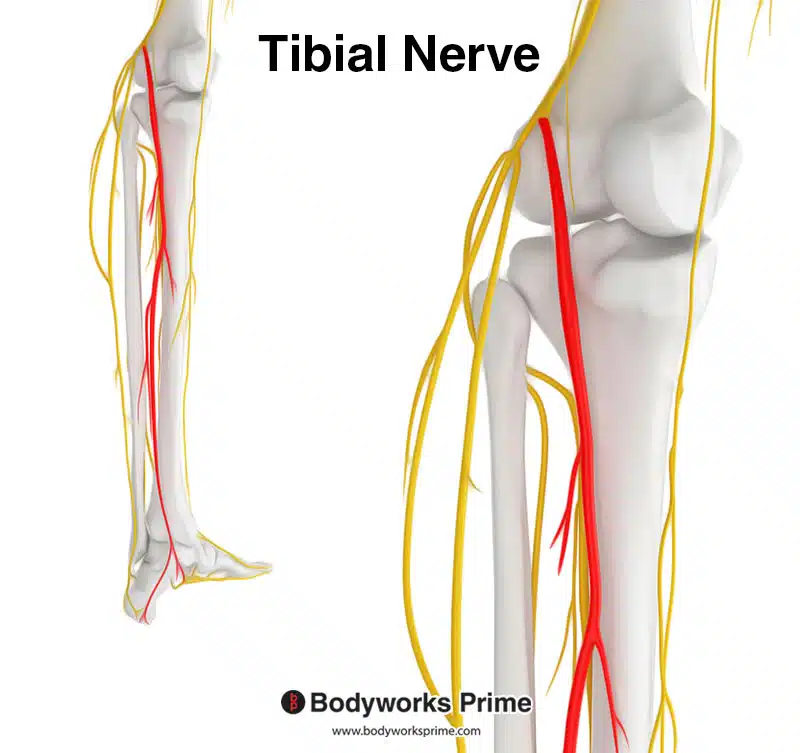

Here we can see the sciatic nerve. Even though the tibial nerve separates from the sciatic nerve just above the knee, it’s important to note that the nerves in our body are organised in a network, not in a strictly linear path. The nerve fibers that will eventually form the tibial nerve are present within the sciatic nerve from the point at which it leaves the spinal cord. These fibers “travel” within the sciatic nerve and reach the muscles they innervate, including the proximal (top) part of the semitendinosus muscle, long before the physical branching of the tibial nerve occurs near the knee. Thus, it’s still accurate to say that the semitendinosus is innervated by the tibial nerve, even though the physical branching occurs distally.

Here we can see the tibial nerve branching off from the sciatic nerve. The tibial division of the sciatic nerve innervates the semitendinosus muscle.

Blood Supply

Blood supply to the semitendinosus muscle is provided primarily by the inferior gluteal artery and the perforating arteries. The inferior gluteal artery is a branch of the internal iliac artery, which supplies blood to the gluteal region and the posterior thigh muscles, including the hamstring muscles. The perforating arteries are branches of the deep femoral artery (profunda femoris) and perforate the adductor magnus muscle to supply blood to the posterior compartment of the thigh [16].

Want some flashcards to help you remember this information? Then click the link below:

Semitendinosus Muscle Flashcards

Support Bodyworks Prime

Running a website and YouTube channel can be expensive. Your donation helps support the creation of more content for my website and YouTube channel. All donation proceeds go towards covering expenses only. Every contribution, big or small, makes a difference!

References

| ↑1, ↑3, ↑5 | Moore KL, Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2017. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑4, ↑6, ↑8, ↑10 | Rodgers CD, Raja A. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hamstring Muscle. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546688/ |

| ↑7, ↑9, ↑11, ↑12, ↑14 | Afonso J, Rocha-Rodrigues S, Clemente FM, et al. The Hamstrings: Anatomic and Physiologic Variations and Their Potential Relationships With Injury Risk. Front Physiol. 2021;12:694604. Published 2021 Jul 7. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.694604 |

| ↑13, ↑15 | Standring S. (2015). Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st Edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier. |

| ↑16 | Tomaszewski KA, Henry BM, Vikse J, Pękala P, Roy J, Svensen M, Guay D, Hsieh WC, Loukas M, Walocha JA. Variations in the origin of the deep femoral artery: A meta-analysis. Clin Anat. 2017 Jan;30(1):106-113. doi: 10.1002/ca.22691. Epub 2016 Feb 2. PMID: 26780216. |