| Origin | Inferior part of the intertrochanteric line Pectineal line (spiral line) Medial lip of the linea aspera Proximal part of the medial supracondylar line Adductor longus muscle Adductor magnus muscle Medial intermuscular septum |

| Insertion | Medial border of the patella Quadricep/patellar tendon The patellar tendon inserts onto the tibial tuberosity |

| Action | Extends the knee |

| Nerve | Femoral nerve (L2, L3, L4) |

| Artery | Femoral artery |

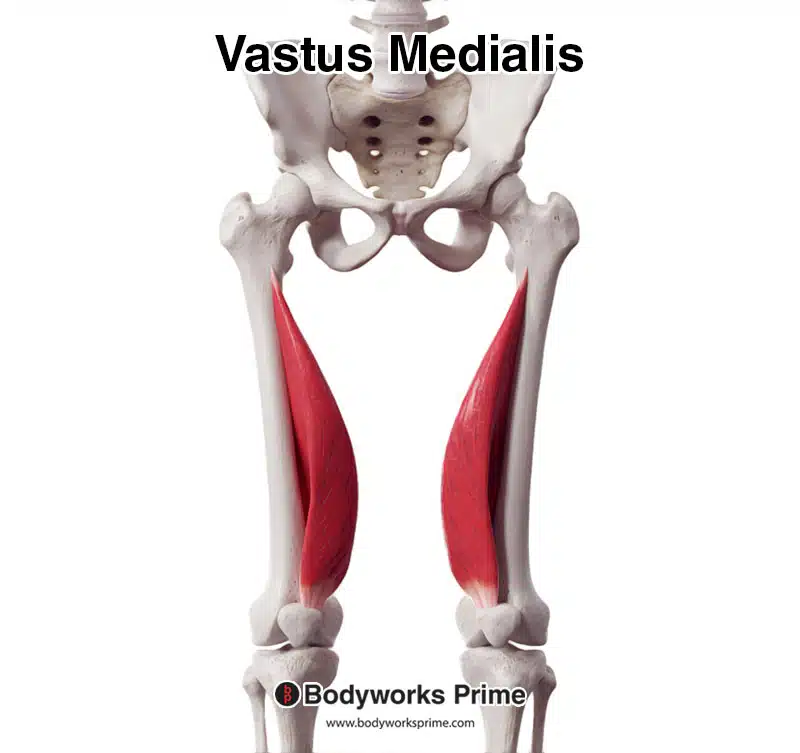

Location & Overview

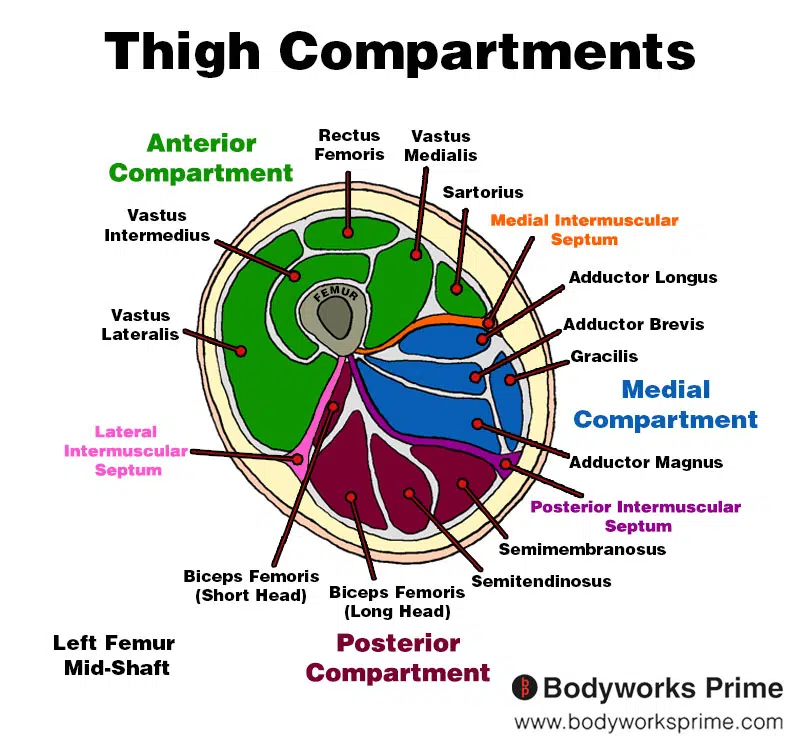

The vastus medialis is a teardrop-shaped muscle that is essential for proper knee joint function [1]. The vastus medialis is the most medial of the four quadriceps muscles, which also include the rectus femoris, vastus intermedius, and the vastus lateralis. Located in the medial thigh, the vastus medialis is part of the anterior compartment of the thigh [2].

The most distal muscle fibers of the vastus medialis are usually referred to as the vastus medialis oblique (VMO) [3]. There has been some debate as to whether the VMO is a separate muscle with its own innervation, as some anatomical studies had not found it to be distinct [4] [5] [6]. However, the presence of the VMO is generally accepted by anatomists and surgeons [7]. Research has shown that the VMO is innervated by a distinct branch of the femoral nerve compared to the rest of the muscle [8]. It is thought that weakness in the VMO can lead to patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), a condition believed to be caused by an imbalance in the activity between the VMO and the vastus lateralis muscle [9]. Other pathologies involving the vastus medialis include muscle strains and contusions [10]. Chondromalacia patella, which is characterised by the softening and degeneration of the cartilage on the back of the patella, may also be related to vastus medialis dysfunction or weakness [11].

To strengthen the vastus medialis, closed kinetic chain exercises, such as squats and lunges, are shown to effectively target the vastus medialis [12]. Leg press can also be a beneficial exercise for targeting the vastus medialis muscle [13] [14].

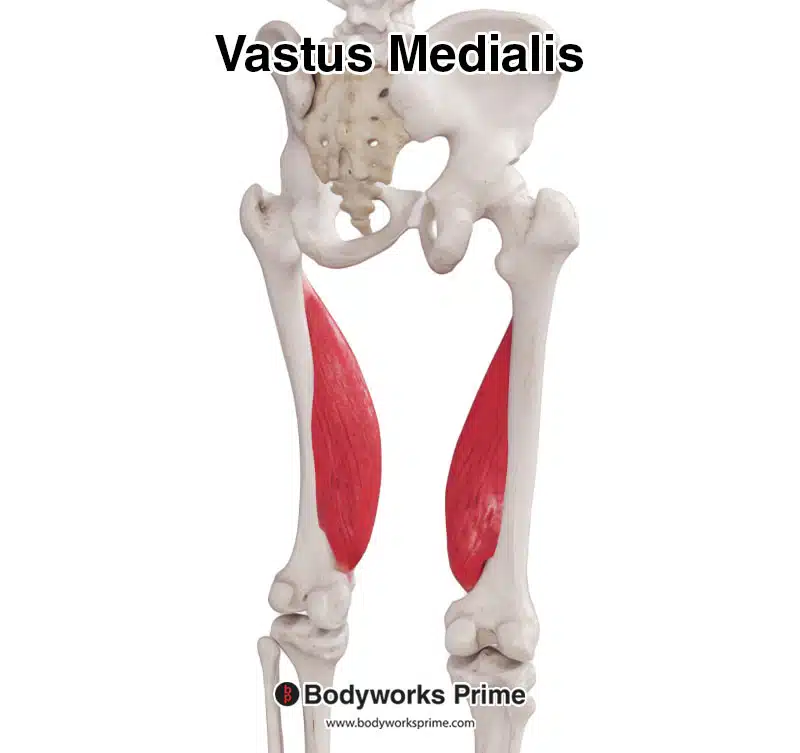

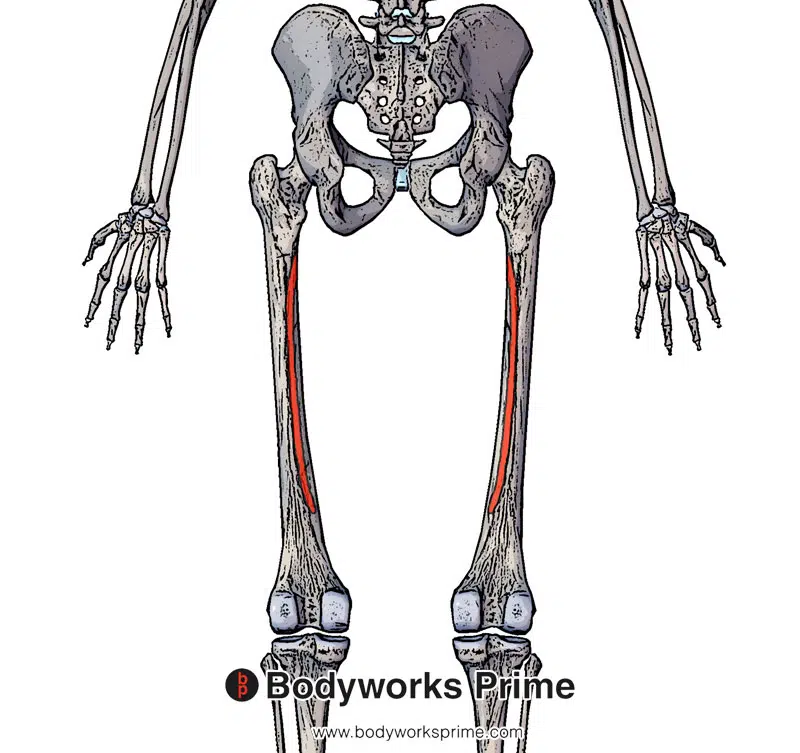

Here we can see the vastus medialis muscle from an anterior view.

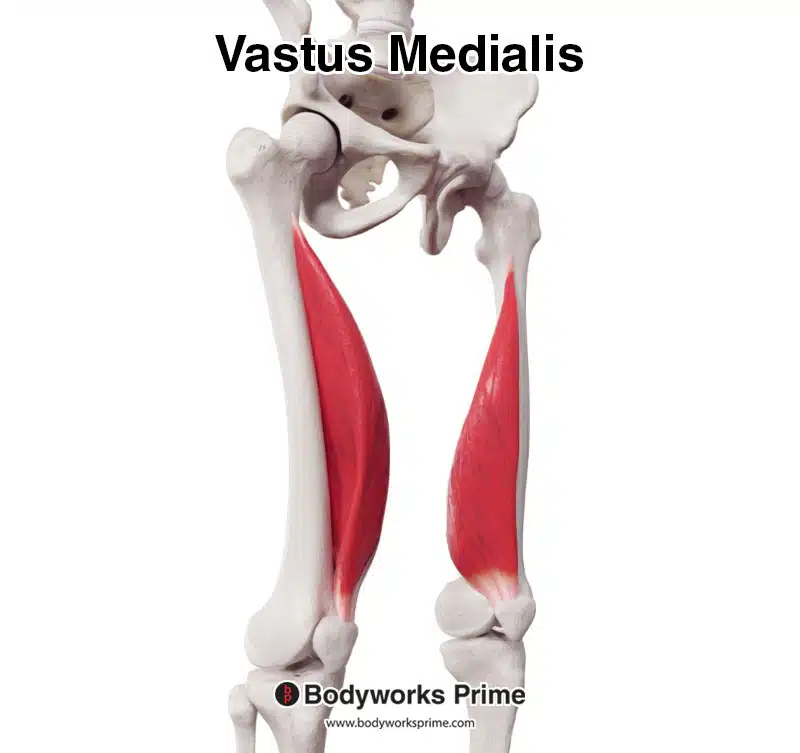

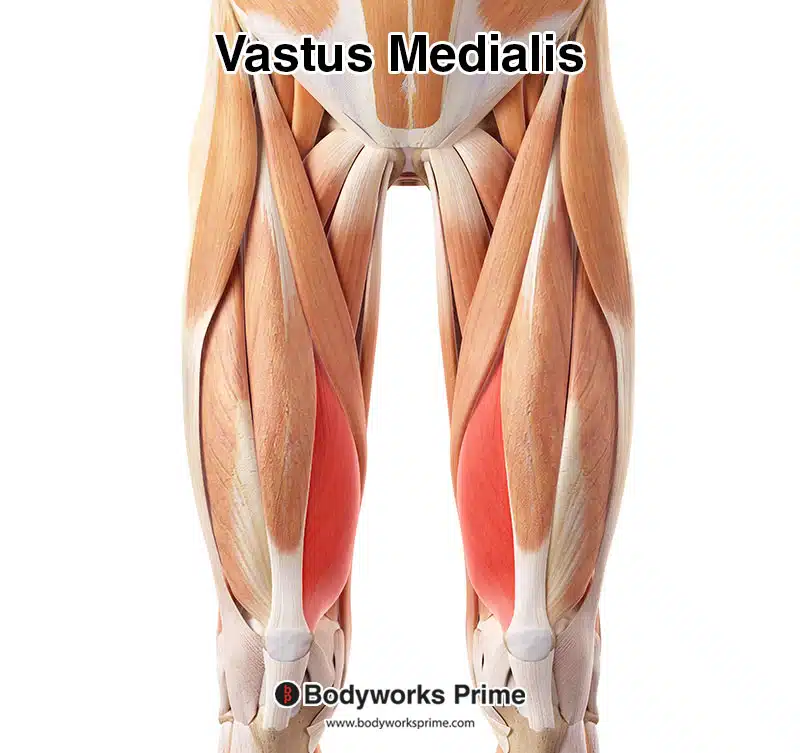

Here we can see the vastus medialis muscle from an anterolateral view.

Here we can see the vastus medialis muscle from a posterior view.

Here we can see the vastus medialis muscle highlighted in red amongst the other muscles of the leg.

Here we can see an image of the compartments of the thigh. We can see the vastus medialis in the anterior compartment, the section coloured in green.

Origin & Insertion

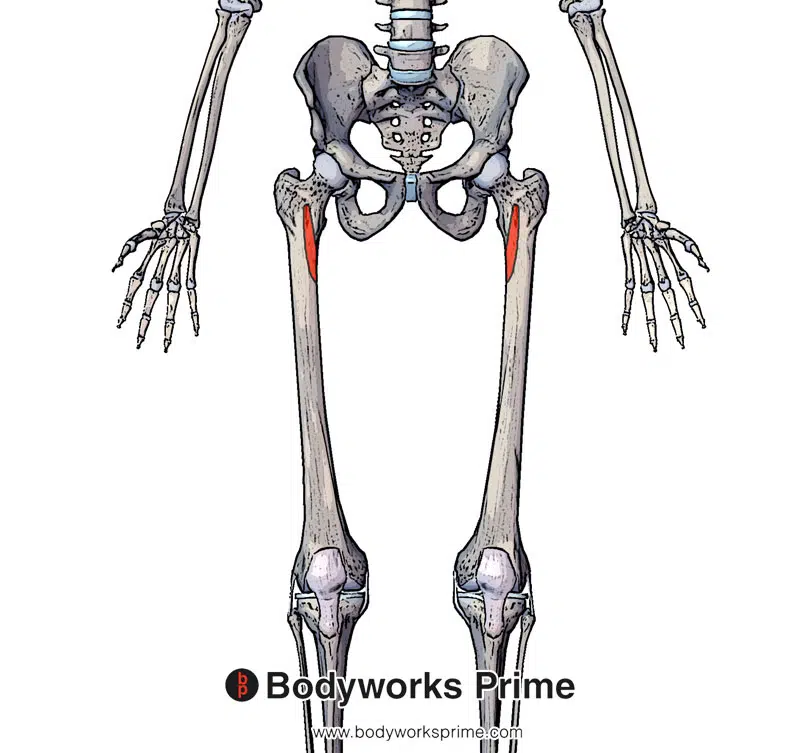

The vastus medialis originates from multiple places on the femur. The first origin is located on the inferior part of the intertrochanteric line, which is a ridge found near the top of the femur [15] [16]. The next is the spiral line, also known as the pectineal line, this is a curved ridge on the medial side of the femur, running inferior and anterior from the lesser trochanter. The medial lip of the linea aspera, a rough ridge on the posterior side of the femur, also serves as an origin for the vastus medialis, as does the proximal part of the medial supracondylar line, which is another ridge found on the posterior side of the femur, near the knee joint. The vastus medialis also originates from the adductor longus and adductor magnus muscles, which are found in the medial thigh, as well as the medial intermuscular septum, a layer of connective tissue separating the thigh’s muscle compartments [17] [18].

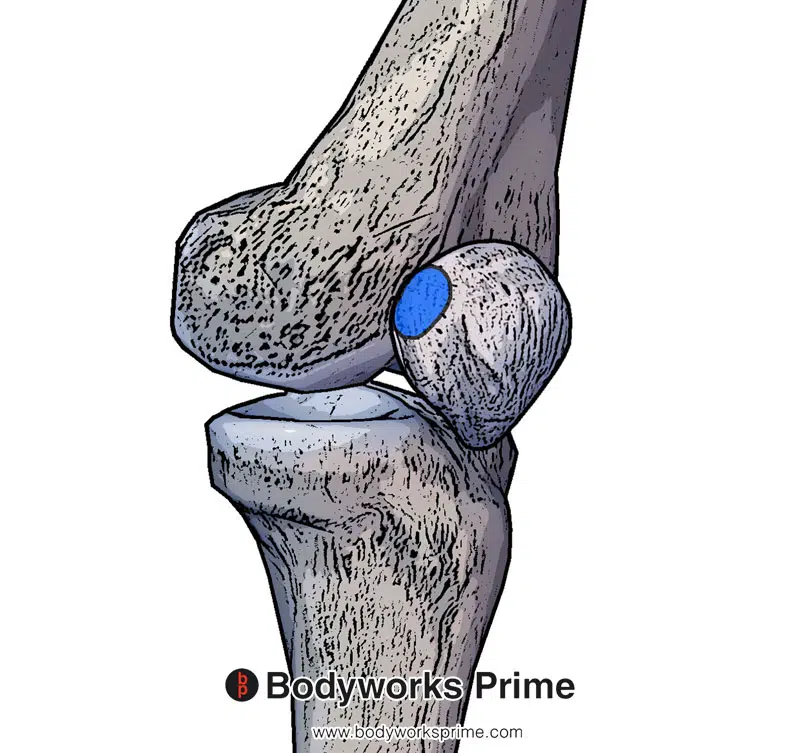

The vastus medialis inserts at the medial border of the patella (kneecap) and also into the quadriceps tendon, which ultimately connects to the tibial tuberosity on the proximal tibia via the patellar ligament [19] [20] [21]. The patellar tendon connects the patella to the tibia, and works together with the quadriceps tendon to facilitate knee extension [22].

Highlighted in red we can see the vastus medialis’ anterior origin points (inferior part of the intertrochanteric line and the spiral line which is also known as the pectineal line).

Highlighted in red we can see the vastus medialis’ posterior origin points (medial lip of the linea aspera and the proximal part of the medial supracondylar line).

Highlighted in blue, we can see the insertion of the patellar tendon. The vastus medialis inserts into the quadriceps tendon which then inserts into the patellar tendon.

Highlighted in blue here we can see another one of the insertion points of the vastus medialis, on the medial side of the patella.

Actions

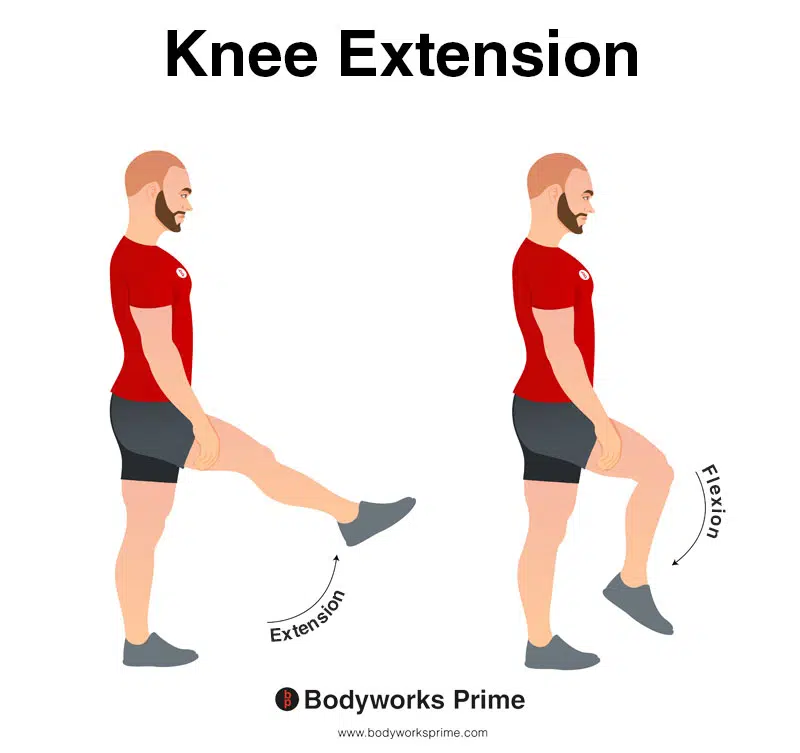

The primary action of the vastus medialis is knee extension, working synergistically with the other quadriceps muscles, including the rectus femoris, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis [23]. The vastus medialis plays an important role in the last 30 degrees of knee extension, by providing stability to the patella during this range of motion [24]. This stabilisation is vital, especially during the terminal phase of knee extension, when the knee is fully extended or close to being fully extended.

In addition to knee extension, the vastus medialis works together with the vastus lateralis to stabilise the knee joint, maintaining proper alignment and preventing excessive lateral movement of the patella [25] [26]. This function is particularly important for the vastus medialis oblique (VMO), the distal muscle fibers of the vastus medialis. This is because these distal muscle fibers are angled more obliquely, to provide better support to the patella [27].

Furthermore, the vastus medialis also has the potential to weakly assist the adductor longus and adductor magnus which perform hip adduction and internal rotation [28]. This is due to the muscle’s medial attachment points on the femur and its connection to the adductor muscles. So, although the vastus medialis does not cross the hip joint itself, it connects to the adductor longus and adductor magnus which do cross the hip joint. However, the the vastus medialis likely plays more of a stabilising role during adduction, rather than directly contributing to the movement.

In this image, you can see an example of knee extension, which is the action of straightening out your leg at the knee. The opposite movement of knee flexion is knee extension. The primary function of the vastus medialis is extension of the knee joint.

Innervation

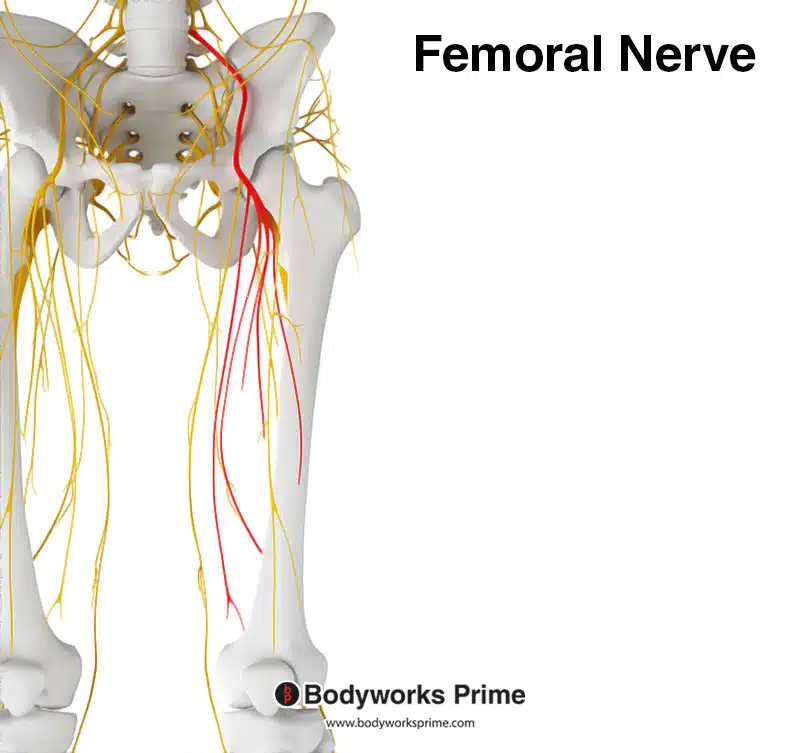

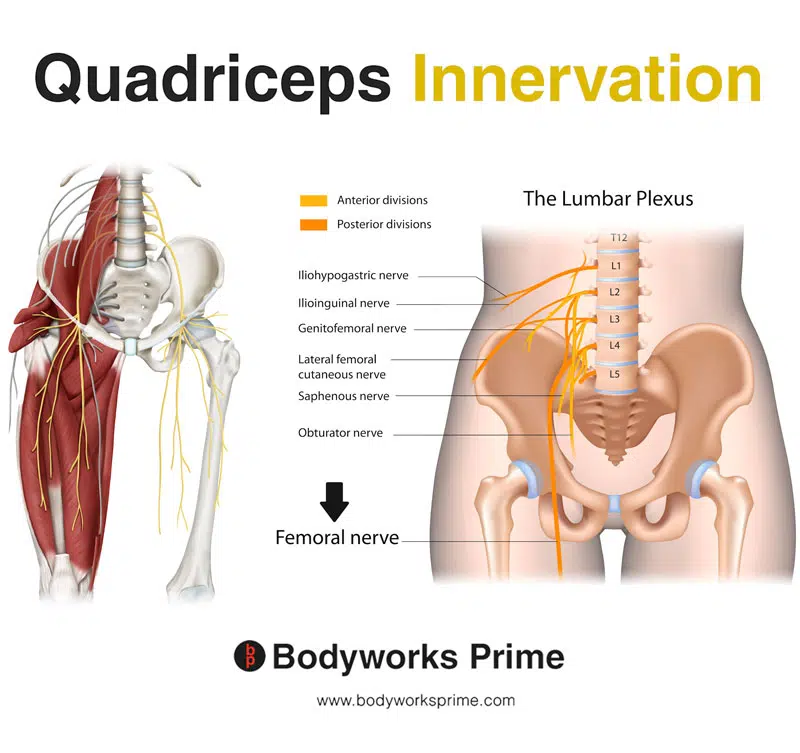

The vastus medialis is innervated by the femoral nerve, which is derived from the lumbar plexus, originating from the spinal nerve roots L2, L3, and L4 [29]. The femoral nerve is one of the main nerves which supplies the muscles of the anterior compartment of the thigh, including the quadriceps muscles. It is responsible for transmitting motor signals from the spinal cord to the vastus medialis, allowing for muscle contraction and movement.

As mentioned earlier, the distal oblique fibers of the vastus medialis, known as the vastus medialis oblique (VMO), have a distinct branch of the femoral nerve that innervates them [30]. This separate innervation allows the VMO to have more precise control over its actions and allows for it to contribute its unique role in patellar stabilisation. Correct function of the VMO is important for maintaining patellar tracking, and weakness or imbalance in its activation compared to the vastus lateralis has been suggested to contribute to patellofemoral pain syndrome [31].

Here we can see the femoral nerve highlighted in red. The femoral nerve innervates the quadriceps muscle group, including the vastus medialis. The femoral nerve originates from the spinal nerve roots of L2, L3, and L4.

Here we can see the innervation of the quadriceps muscle group, the femoral nerve is a major branch of the lumbar plexus.

Blood Supply

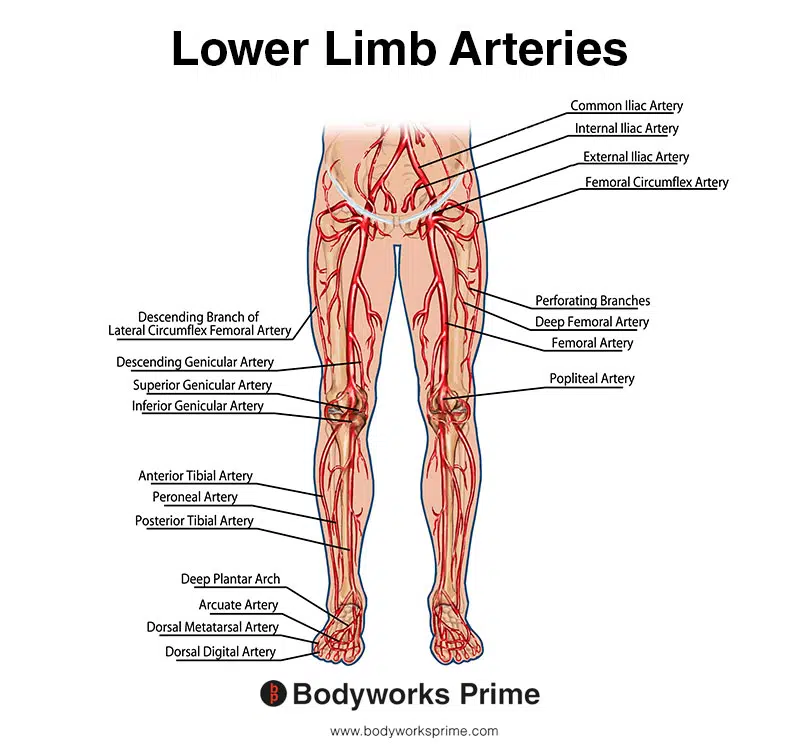

Blood is supplied to the vastus medialis from the superficial femoral artery as well as the deep femoral artery [32].

This image shows the arteries of the lower limb, including the femoral artery.

Want some flashcards to help you remember this information? Then click the link below:

Vastus Medialis Flashcards

Support Bodyworks Prime

Running a website and YouTube channel can be expensive. Your donation helps support the creation of more content for my website and YouTube channel. All donation proceeds go towards covering expenses only. Every contribution, big or small, makes a difference!

References

| ↑1, ↑15, ↑17, ↑22 | Moore KL, Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2017. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑3, ↑7 | Waligora AC, Johanson NA, Hirsch BE. Clinical anatomy of the quadriceps femoris and extensor apparatus of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009 Dec;467(12):3297-306. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1052-y. Epub 2009 Aug 19. PMID: 19690926; PMCID: PMC2772911. |

| ↑4 | Hubbard JK, Sampson HW, Elledge JR. Prevalence and morphology of the vastus medialis oblique muscle in human cadavers. Anat Rec. 1997 Sep;249(1):135-42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199709)249:1<135::AID-AR16>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID: 9294658. |

| ↑5 | Lefebvre R, Leroux A, Poumarat G, Galtier B, Guillot M, Vanneuville G, Boucher JP. Vastus medialis: anatomical and functional considerations and implications based upon human and cadaveric studies. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006 Feb;29(2):139-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.12.006. PMID: 16461173. |

| ↑6 | Peeler J, Cooper J, Porter MM, Thliveris JA, Anderson JE. Structural parameters of the vastus medialis muscle. Clin Anat. 2005 May;18(4):281-9. doi: 10.1002/ca.20110. PMID: 15832351. |

| ↑8, ↑19, ↑29, ↑30 | Toumi H, Poumarat G, Benjamin M, Best TM, F’Guyer S, Fairclough J. New insights into the function of the vastus medialis with clinical implications. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Jul;39(7):1153-9. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0b013e31804ec08d. Erratum in: Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 May;40(5):982. Best, Thomas [corrected to Best, Thomas M]. PMID: 17596784. |

| ↑9, ↑31 | Waryasz GR, McDermott AY. Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS): a systematic review of anatomy and potential risk factors. Dyn Med. 2008 Jun 26;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-5918-7-9. PMID: 18582383; PMCID: PMC2443365. |

| ↑10 | Benjamin M, Kaiser E, Milz S. Structure-function relationships in tendons: a review. J Anat. 2008 Mar;212(3):211-28. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00864.x. PMID: 18304204; PMCID: PMC2408985. |

| ↑11 | Dixit S, DiFiori JP, Burton M, Mines B. Management of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Jan 15;75(2):194-202. PMID: 17263214. |

| ↑12 | Escamilla RF, Fleisig GS, Zheng N, Lander JE, Barrentine SW, Andrews JR, Bergemann BW, Moorman CT 3rd. Effects of technique variations on knee biomechanics during the squat and leg press. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 Sep;33(9):1552-66. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200109000-00020. PMID: 11528346. |

| ↑13 | Martín-Fuentes I, Oliva-Lozano JM, Muyor JM. Influence of Feet Position and Execution Velocity on Muscle Activation and Kinematic Parameters During the Inclined Leg Press Exercise. Sports Health. 2022 May-Jun;14(3):317-327. doi: 10.1177/19417381211016357. Epub 2021 Jun 4. PMID: 34085847; PMCID: PMC9112713. |

| ↑14 | Wilk KE, Escamilla RF, Fleisig GS, Barrentine SW, Andrews JR, Boyd ML. A comparison of tibiofemoral joint forces and electromyographic activity during open and closed kinetic chain exercises. Am J Sports Med. 1996 Jul-Aug;24(4):518-27. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400418. PMID: 8827313. |

| ↑16, ↑18 | Rajput HB, Rajani SJ, Vaniya VH. Variation in Morphometry of Vastus Medialis Muscle. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Sep;11(9):AC01-AC04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/29162.10527. Epub 2017 Sep 1. PMID: 29207687; PMCID: PMC5713709. |

| ↑20 | Standring S. (2015). Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st Edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier. |

| ↑21 | Sonin AH, Fitzgerald SW, Bresler ME, Kirsch MD, Hoff FL, Friedman H. MR imaging appearance of the extensor mechanism of the knee: functional anatomy and injury patterns. Radiographics. 1995 Mar;15(2):367-82. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.15.2.7761641. PMID: 7761641. |

| ↑23, ↑25 | Hyong IH, Kang JH. Activities of the Vastus Lateralis and Vastus Medialis Oblique Muscles during Squats on Different Surfaces. J Phys Ther Sci. 2013 Aug;25(8):915-7. doi: 10.1589/jpts.25.915. Epub 2013 Sep 20. PMID: 24259884; PMCID: PMC3820212. |

| ↑24 | Irish SE, Millward AJ, Wride J, Haas BM, Shum GL. The effect of closed-kinetic chain exercises and open-kinetic chain exercise on the muscle activity of vastus medialis oblique and vastus lateralis. J Strength Cond Res. 2010 May;24(5):1256-62. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181cf749f. PMID: 20386128. |

| ↑26, ↑27 | Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Thigh Quadriceps Muscle. 2021 Jul 22. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 30020706. |

| ↑28 | Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the hip: a focus on muscular actions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010 Feb;40(2):82-94. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3025. PMID: 20118525. |

| ↑32 | Jordan JA, Burns B. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Hip Arteries. [Updated 2021 Jul 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542174/ |