| Origin | Anterior surface and medial half of clavicle (clavicular head) Anterior surface of sternum (sternocostal head) Superior six costal cartilages (sternocostal head) Aponeurosis of external oblique muscle (sternocostal head) |

| Insertion | The lateral lip of the bicipital groove |

| Action | Adduction of humerus at shoulder joint Medial rotation of humerus at shoulder joint Flexion of humerus at shoulder joint (clavicular head) Extension of humerus at shoulder joint (sternocostal head) |

| Nerve | Medial pectoral nerve (C8 & T1) Lateral pectoral nerve (C5, C6, & C7) |

| Artery | Pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery |

Location & Overview

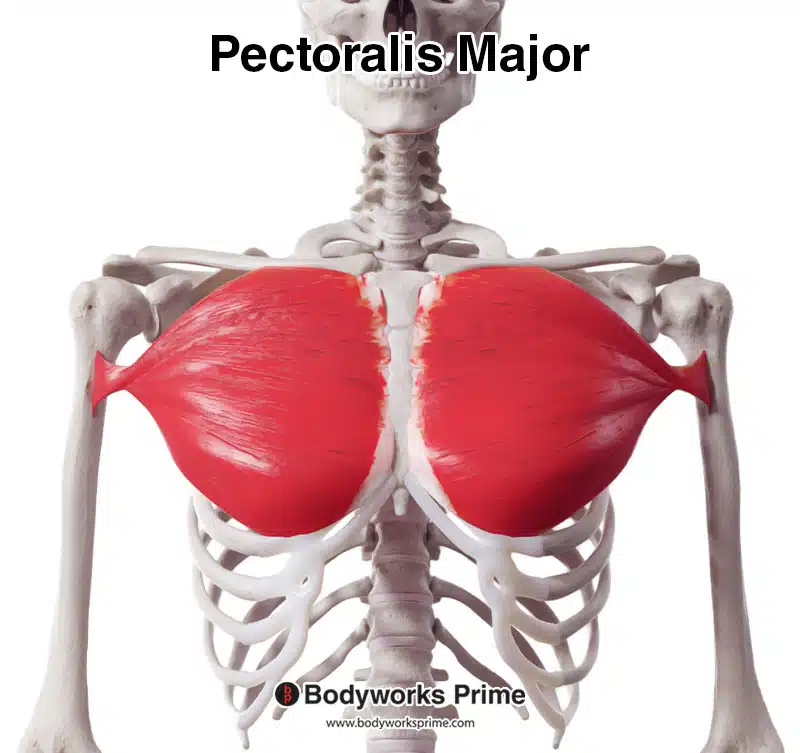

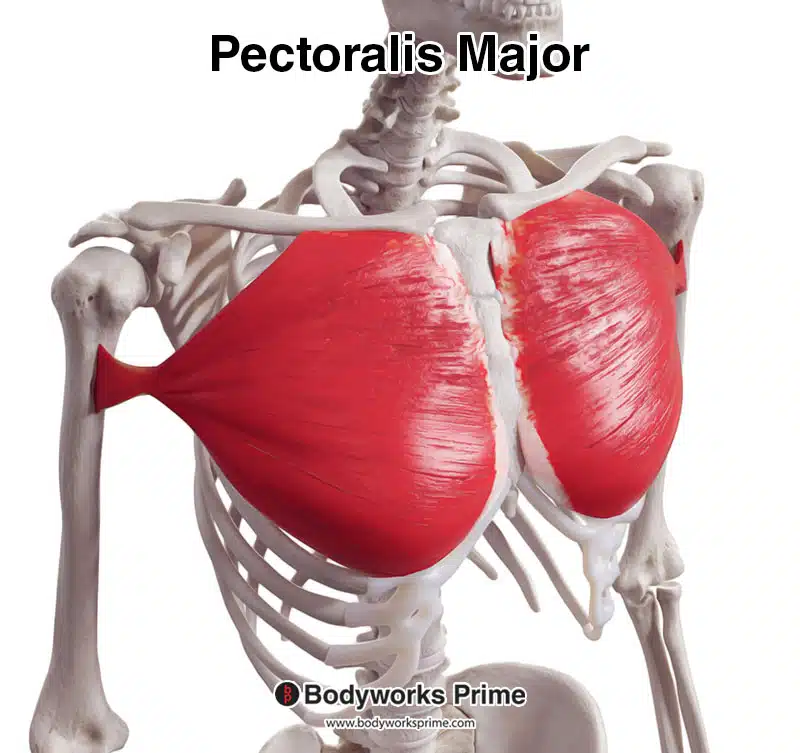

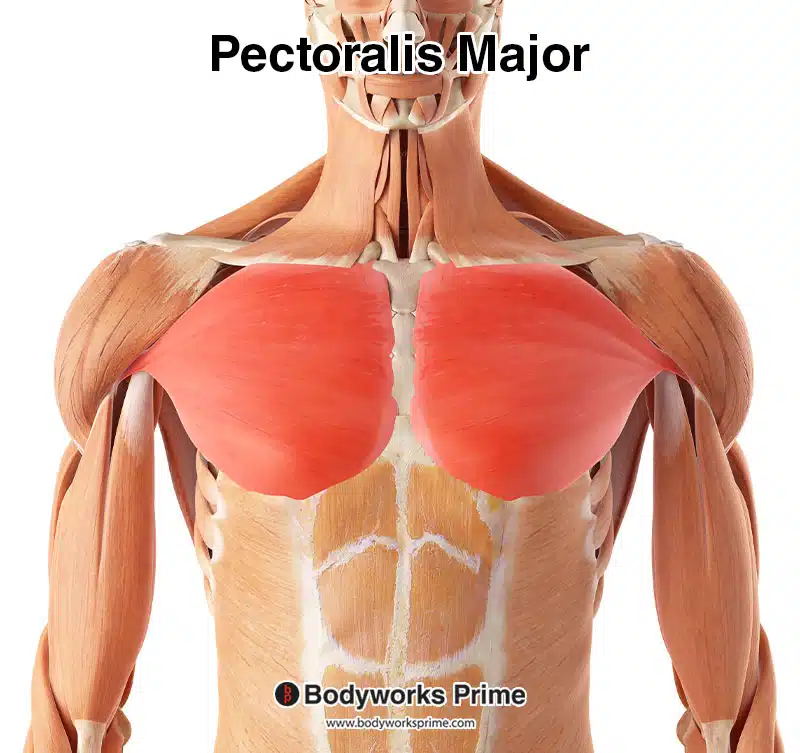

The pectoralis major, often colloquially referred to as the ‘pecs’, is an expansive muscle that covers the anterior chest wall. The pectoralis major is the most superficial muscle in the pectoral region. It serves as the anterior wall of the axilla (armpit), and forms a large part of the contour of the chest [1] [2].

This large, fan-shaped muscle is located between the subcutaneous tissue and the deeper pectoralis minor muscle and laterally the serratus anterior. It extends laterally towards the deltoid muscle at the shoulder. The pectoralis major spans across the chest, extending from the sternum and clavicle (medial side) to the upper portion of the humerus (lateral side). It is also positioned superiorly to the rectus abdominis and the oblique muscles of the abdomen [3] [4] [5] [6].

The pectoralis major is functionally and anatomically divided into two distinct parts: the clavicular head and the sternal head. The clavicular head is comprised of the superior portion, closest to the clavicle. The sternocostal head is the inferior portion, originating from the sternum. Both heads converge as they insert at the lateral lip of the bicipital groove of the humerus [7] [8] [9] [10].

Here we can see the pectoralis major muscle from an anterior view.

Here we can see the pectoralis major muscle from an anterolateral view.

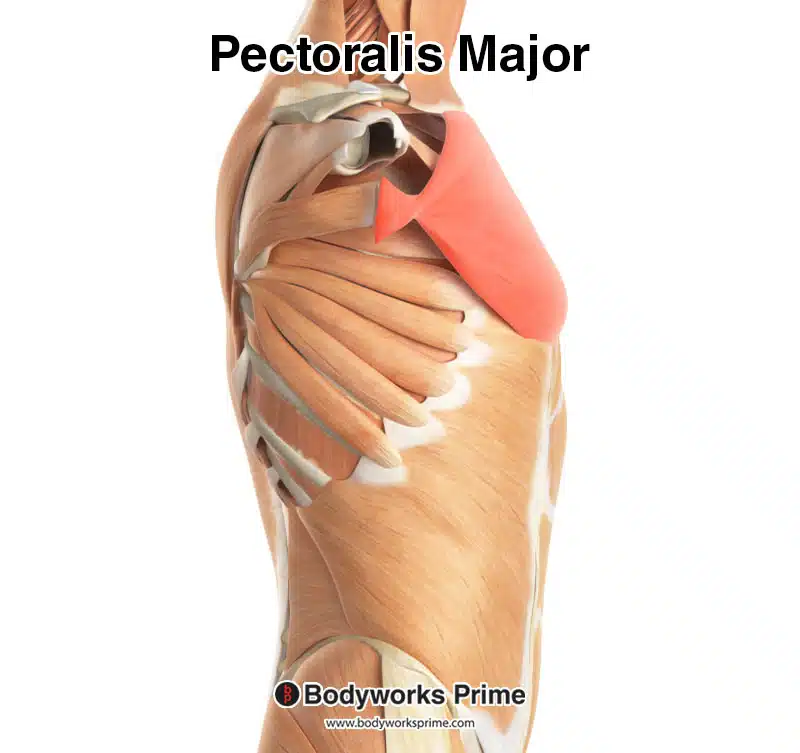

Here we can see the pectoralis major muscle from a lateral view.

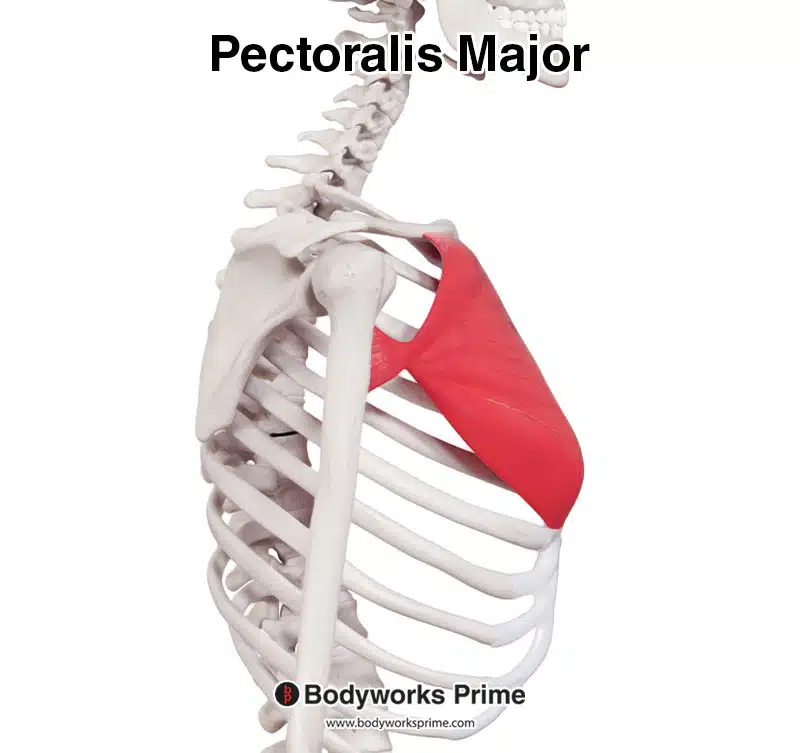

Here we can see the pectoralis major muscle, highlighted in red, seen from a lateral view.

Here we can see the pectoralis major muscle, highlighted in red, seen from an anterior view.

Origin & Insertion

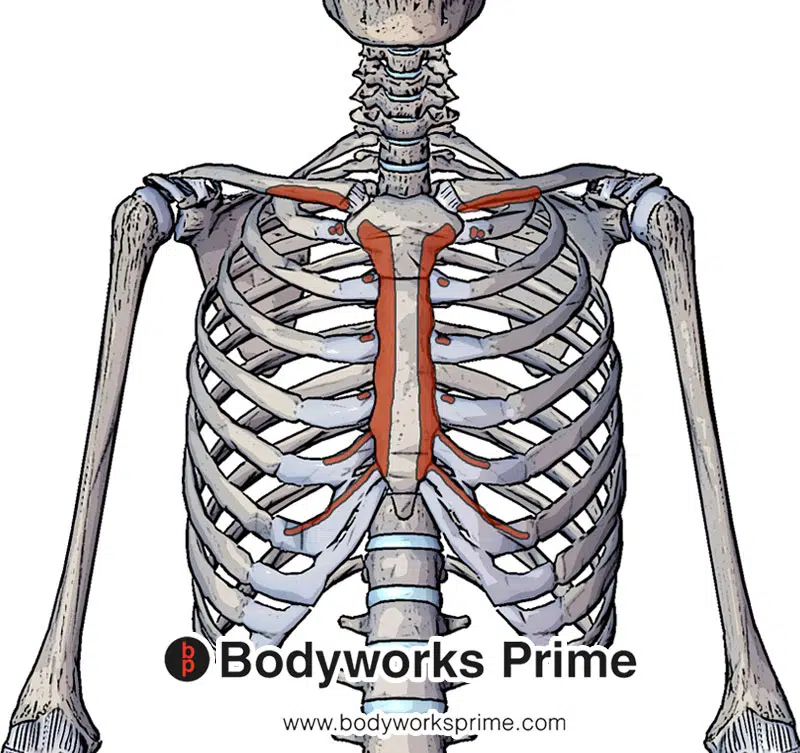

The pectoralis major has a broad origin from several points along the medial and superior aspects of the chest wall. The clavicular head of the pectoralis major originates from the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle. The clavicle is a long bone that runs horizontally across the top part of the chest, forming part of the shoulder. The clavicle can be easily palpated, providing an accessible landmark for understanding the superior aspect of the muscle’s origin [11] [12].

The sternocostal head has a more expansive origin, which begins at the anterior surface of the sternum. The sternum (or breastbone) is a long and flat bone located at the centre of the chest. The sternum connects to the ribs via cartilage, forming the anterior section of the rib cage and providing a surface for the origin of the pectoralis major’s sternocostal head. The sternocostal head also originates on the superior six costal cartilages, these costal cartilages connect the ribs to the sternum [13] [14].

The pectoralis major muscle also originates from the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. The external oblique is one of the outermost abdominal muscles. It’s located on the lateral and anterior parts of the abdomen [15]. The aponeurosis of the external oblique is a flat, is the broad, flat tendinous portion of the muscle. This aponeurosis provides another site for the pectoralis major’s origin [16].

As the sternal and clavicular head’s fibers travel laterally, they converge to form its common tendon which inserts onto the lateral lip of the bicipital groove of the humerus, also known as the intertubercular groove [17] [18]. The bicipital groove is a deep groove that runs down the front of the humerus, housing the tendon of the biceps brachii muscle [19].

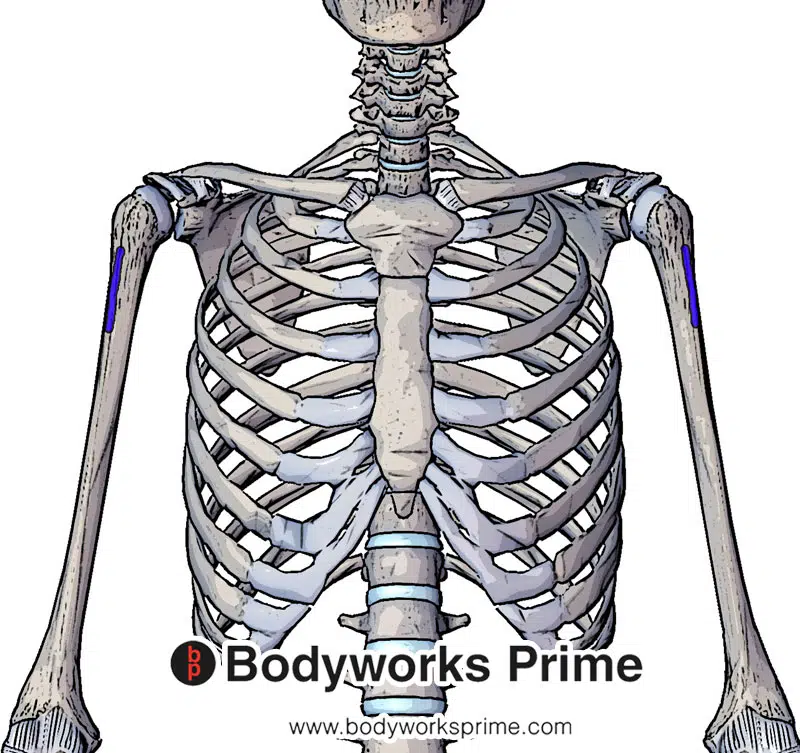

Here we can see the origins of the pectoralis major muscle at the anterior surface and the medial half of clavicle, the anterior surface of sternum and the superior six costal cartilages.

Here we can see the insertion of the pectoralis major muscle at the lateral lip of the bicipital groove.

Actions

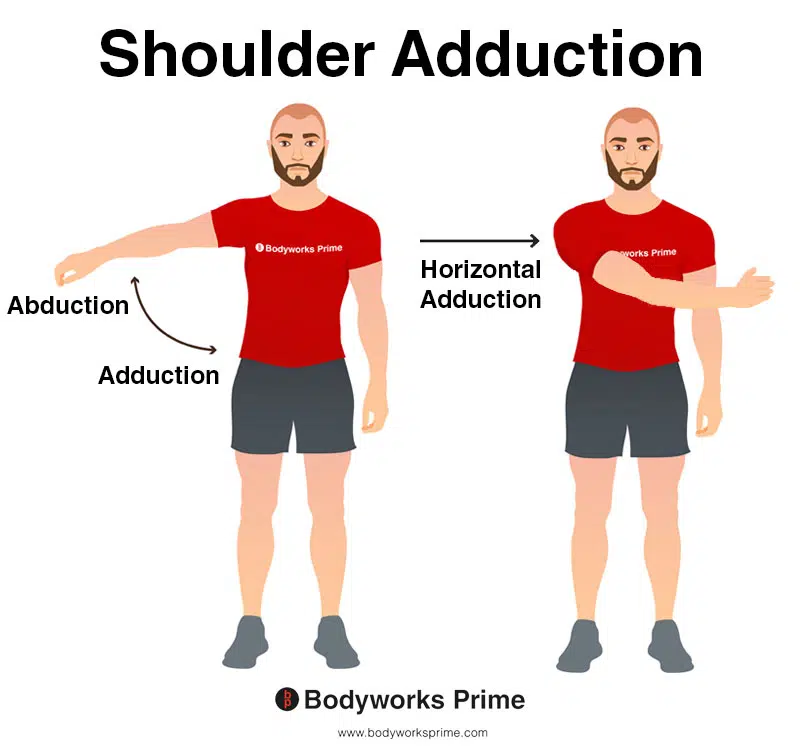

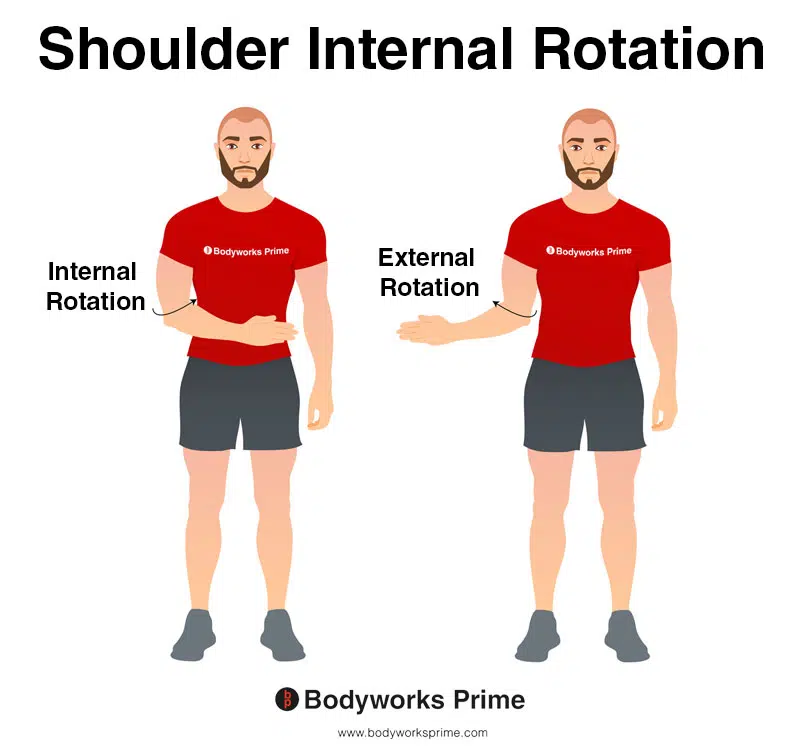

The actions of the pectoralis major muscle are determined by which section of the muscle is contracting. Both the clavicular and the sternocostal heads are involved in adduction of the humerus at the shoulder joint [20]. An example of this is moving the humerus across the body, such as during a bench press or a dumbbell chest fly. Both heads are also involved in medial (internal) rotation of the humerus at the shoulder joint, which is where the humerus rotates towards the midline of the body [21].

This image features two types of shoulder adduction. On the left, the individual is performing standard shoulder adduction, where the arm is brought towards the midline of the body, reducing the angle between the arm and the torso. On the right, the individual is demonstrating horizontal shoulder adduction, a similar movement performed parallel to the ground in the transverse plane. Both movements engage the pectoralis major, among other muscles. The opposite of adduction is abduction, which occurs as the arm is moved away from the midline, increasing the angle between the arm and the torso.

This image shows shoulder internal rotation. Internal rotation is when the humerus is rotated inward toward the centre of the body, towards the body’s midline. The opposite of this is external rotation, which is when humerus is rotated outward away from the centre of the body, away from the body’s midline. Internal rotation is also known as medial rotation and external rotation is also known as lateral rotation. Both heads are involved in medial (internal) rotation of the humerus at the shoulder joint.

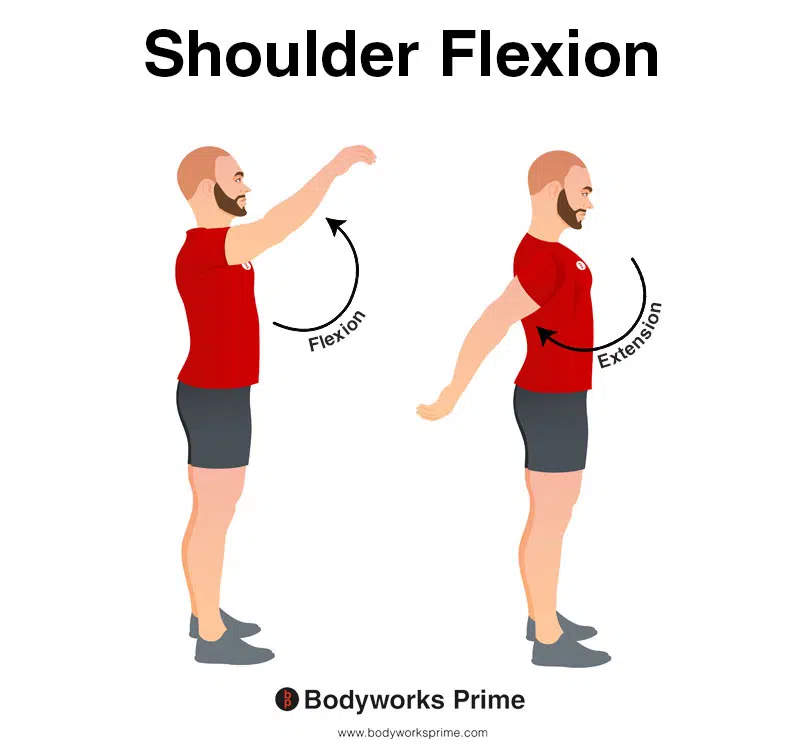

The clavicular head of the pectoralis major is involved in the flexion of the humerus at the shoulder joint, which is the movement of bringing the arm forward and upwards [22]. This is the reason why exercises such as the incline bench press are typically used to focus on the clavicular head, as this movement involves both adduction and flexion of the humerus at the shoulder joint. This movement has a slightly greater degree of shoulder flexion compared to, for example, the flat bench press. This increased shoulder flexion increases the involvement of the clavicular head, provided the bench is set at a suitably high angle. Trebs et al. (2010) found that the clavicular head of the pectoralis major experienced significantly heigher activity at bench angles of 44° and 56° but not 28° [23].

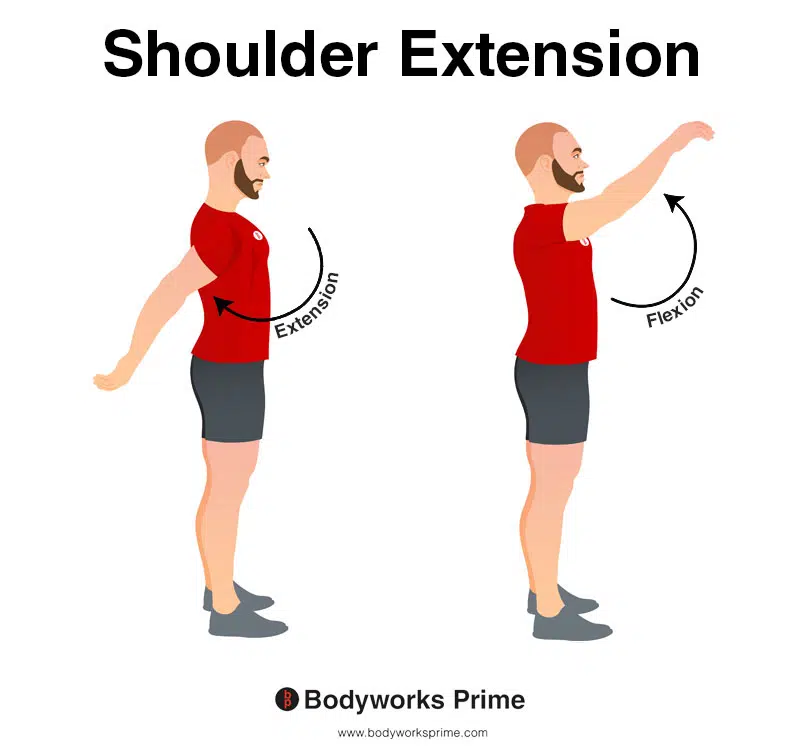

This image shows shoulder flexion. Flexion is where the arm is moved forward and upward in an anterior direction. The opposite of this is shoulder extension, which occurs as the arm is moved backward in a posterior direction. The clavicular head of the pectoralis major is involved in the flexion of the humerus at the shoulder joint.

The sternocostal head of the muscle also contributes to the extension of the humerus at the shoulder joint [24]. Shoulder extension involves moving the raised arm downwards towards the body. This contribution to extension by the sternocostal head of the pectoralis major is most notable when the shoulder is flexed, such as when the arms are raised overhead. Therefore, in the initial hanging phase of a pull-up, the sternocostal portion of the pectoralis major does have some minor involvement in extending the humerus. However, the predominant muscles of this movement are still going to be the muscles of the back, such as the latissimus dorsi, teres major, and posterior deltoid. Once the arm reaches the anatomical position (humerus by the side of the body), the pectoralis major no longer contributes to shoulder extension. The forces contributed by the pec major to extension also diminish as the humerus gets closer to reaching this position. This is why its involvement is most notable when the shoulder is flexed.

This image shows shoulder extension. Extension is where the arm is moved backward in a posterior direction (towards the back of the body), increasing the angle between the arm and the torso in the sagittal plane. The opposite of this is shoulder flexion which occurs as the arm is moved forward and upward in an anterior direction. The sternocostal head of the muscle also contributes to the extension of the humerus at the shoulder joint. This contribution to extension by the sternocostal head of the pectoralis major is most notable when the shoulder is flexed. Once the arm reaches the anatomical position (humerus by the side of the body), the pectoralis major no longer contributes to shoulder extension.

Innervation

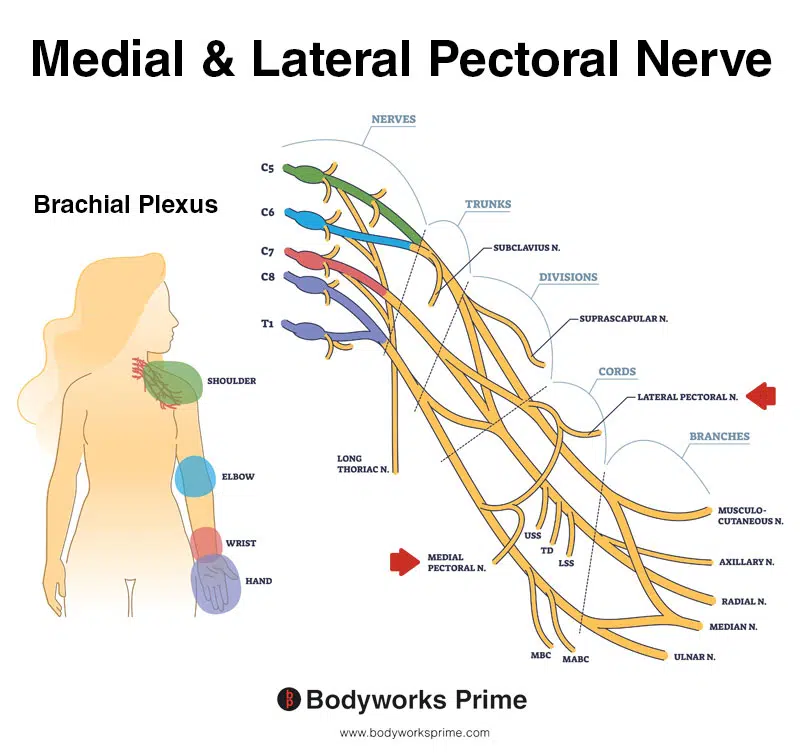

The pectoralis major muscle is composed of two distinct heads. The clavicular and sternal heads receive their neural inputs from two different nerves. The clavicular head is innervated by the lateral pectoral nerve, while the sternocostal head gets its innervation from the medial pectoral nerve [25] [26] [27].

The lateral pectoral nerve originates directly from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. It then proceeds anteriorly to the axillary artery, positioning itself on the medial side of the muscle’s humeral insertion. This nerve then courses along the posterior surface of the pectoralis major muscle, providing its innervation [28] [29].

The medial pectoral nerve arises from the medial cord of the brachial plexus. It travels posteriorly to the axillary artery. The medial pectoral nerve makes its entry into the muscle complex by piercing the pectoralis minor near the midclavicular line. Following this, it branches off and settles on the posterior surface of the pectoralis major muscle which facilitates its various motor functions [30] [31].

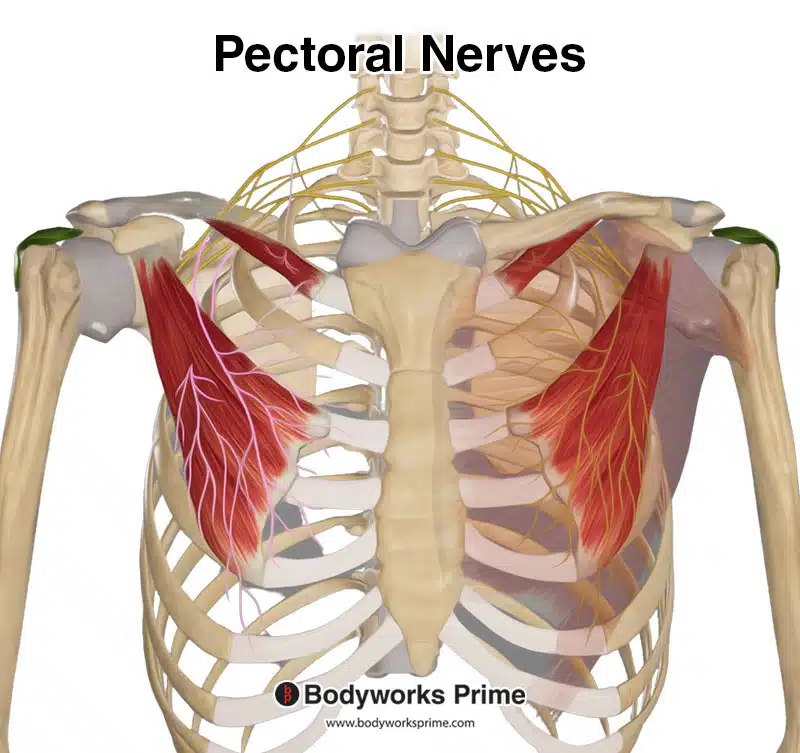

Pictured here you can see the medial and lateral pectoral nerves alongside the brachial plexus. The pectoralis major muscle is innervated by the medial pectoral nerve and the lateral pectoral nerve.

Pictured here you can medial and lateral pectoral nerves which innervate both the pectoralis major and minor.

Blood Supply

The main arterial supply to the pectoralis major muscle is provided by the thoracoacromial artery, a major artery found in the upper chest region. This artery originates from the second part of the axillary artery. The axillary artery bifurcates into various branches. These include the acromial, deltoid, clavicular, and pectoral branches, each supplying blood to the corresponding areas of the upper body. Specifically, the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery provides delivery of oxygenated blood to the pectoralis major muscle [32] [33].

Want some flashcards to help you remember this information? Then click the link below:

Pectoralis Major Flashcards

Support Bodyworks Prime

Running a website and YouTube channel can be expensive. Your donation helps support the creation of more content for my website and YouTube channel. All donation proceeds go towards covering expenses only. Every contribution, big or small, makes a difference!

References

| ↑1, ↑5, ↑9, ↑19, ↑28, ↑30 | Standring S. (2015). Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st Edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑6, ↑10, ↑16, ↑29, ↑31 | Moore KL, Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2017. |

| ↑3, ↑7, ↑26 | Haley CA, Zacchilli MA. Pectoralis major injuries: evaluation and treatment. Clin Sports Med. 2014 Oct;33(4):739-56. |

| ↑4, ↑8, ↑27 | Sanchez ER, Sanchez R, Moliver C. Anatomic relationship of the pectoralis major and minor muscles: a cadaveric study. Aesthet Surg J. 2014 Feb;34(2):258-63. |

| ↑11, ↑13, ↑15, ↑17 | Baig MA, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Pectoral Muscles. [Updated 2022 Aug 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545241/ |

| ↑12, ↑14, ↑18, ↑20, ↑21, ↑22, ↑24, ↑25 | Solari F, Burns B. Anatomy, Thorax, Pectoralis Major Major. [Updated 2022 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525991/ |

| ↑23 | Trebs A.A., Brandenburg J.P., Pitney W.A. An electromyography analysis of 3 muscles surrounding the shoulder joint during the performance of a chest press exercise at several angles. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010;24:1925–1930. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181ddfae7. |

| ↑32 | Nakajima K, Ide Y, Abe S, Okada M, Kikuchi A, Ide Y. Anatomical study of the pectoral branch of thoracoacromial artery. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 1997 Aug;38(3):207-15. PMID: 9566136. |

| ↑33 | Bonczar M, Gabryszuk K, Ostrowski P, Batko J, Rams DJ, Krawczyk-Ożóg A, Wojciechowski W, Walocha J, Koziej M. The thoracoacromial trunk: a detailed analysis. Surg Radiol Anat. 2022 Oct;44(10):1329-1338. doi: 10.1007/s00276-022-03016-4. Epub 2022 Sep 12. PMID: 36094609; PMCID: PMC9649491. |